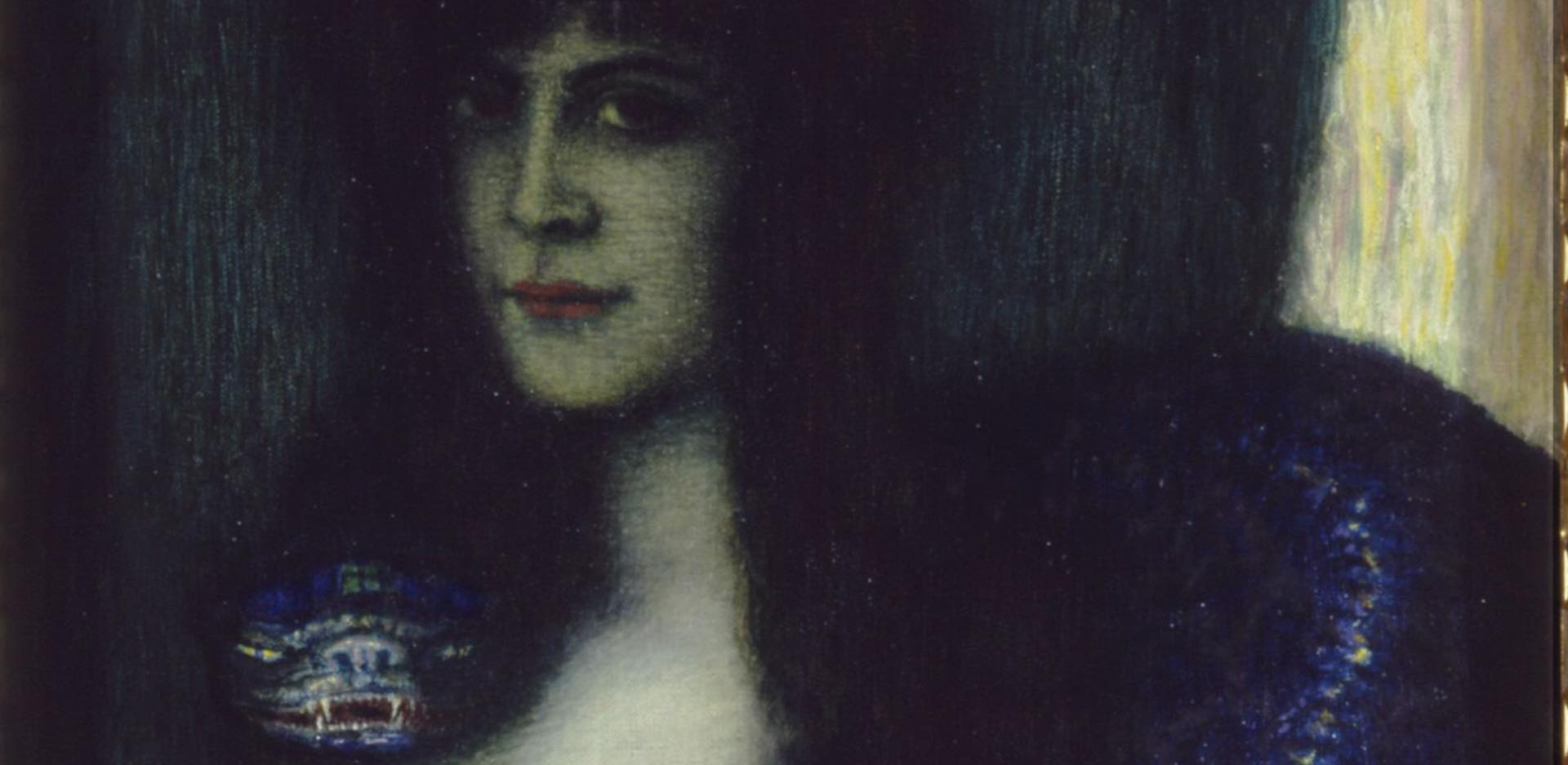

Some works of art contain a force that cannot be reckoned at the moment of first encounter. Their power lies dormant, a seed cast into the loam of one’s own threshold, only later to emerge, transfigured and quietly menacing, from the night of unknowing. Such was the effect of Franz von Stuck’s Die Sünde, that ambiguous threshold between the sacred and the forbidden, whose gaze troubled the chambers of a particular night-room where the soul, trembling, lay down to its symbolic death. In those days, the painting watched, an oracle silent and undeciphered; a presence, certainly, but one whose power remained veiled, incomplete, a surface whose most insidious current swam unseen below the sheen of oil and greenish flesh. One could, in those first weeks, believe the secret lay in the eyes, in the curve of the shoulder, in the unashamed confrontation of flesh and shadow. The true heart of the matter was nevertheless hidden – a coiled absence that took its time to emerge and ,when it did, it was as though a lock, long untouched, had turned within the wood.

It is necessary, before proceeding, to evoke the air of the epoch that gave rise to such an image; for Symbolism, as a movement, arose in the twilight of the 19th century, under the shadow of disillusionment and the quest for new mysteries. Its artists, priests of ambiguity and fugitives from positivism, convened not in the blinding clarity of academies, but in rooms scented with myrrh, perfumed by decay and illuminated by the flicker of obsidian lamps. In Paris, the Salon Rose-Croix, under the orchestration of Péladan, conjured a world where symbol, myth, and rite mingled in the thick, perfumed air, where art was altar and vision was invocation. It was in such a crucible that Die Sünde found its spiritual kin: there every curve and shadow signified more than flesh, every detail harboured a secret invitation. The gaze of the painted woman, half-accusation and half-confession, was the surface. The deeper current moved elsewhere, in the slow undulation of forms at the threshold of awareness.

I. The Patient Veil: On What Lurks in Shadow

There is a species of vision which only discloses its true nature in the aftermath of encounter. One may spend days, even weeks, in the presence of a painting, convinced that its secret has already been assimilated, when, in truth, the image works upon the psyche with subterranean patience, fashioning a corridor beneath the skin through which its charge will later surge. This was precisely the case with the serpent of Die Sünde. A form so inextricable from the flesh it coils around that it at first eludes the gaze entirely, camouflaged in chromatic kinship with the shadows of the room and the blue-green undertone of the flesh. One can live in the company of that gaze, meditate upon the geometry of the limbs, the poise of the neck, even dream the figure into one’s most private theatre, and yet remain blind to the latent intelligence encircling the subject. The serpent is patient. It abides in shadow, biding its hour, allowing the viewer to linger in partial comprehension, to believe, perhaps, that the essence of the painting is exposure, the fearless unmasking of desire. But this is only the first ring; the real ordeal is reserved for those who remain. For the serpent will not betray itself to the hasty or the hungry; it reveals itself only to those who survive the gaze and remain to witness the movement in the undergrowth.

II. The Moment of Recognition: Serpent as Ancient Glyph

When, at last, the serpent is seen, the revelation is retrospective. Suddenly the entire field of vision rearranges itself around the curve of the reptilian body, the hand that clasps it as if in long complicity, the flesh that no longer stands alone but is marked, marked by the cold wisdom of ancient days. The serpent is never mere accessory; it is ancestral, the sigil of all that is occluded and yet essential. Its appearance, delayed and almost reluctant, is an act of symbolic initiation. One is reminded that the serpent, from Eden to Delphi, from the crown of Egyptian pharaohs to the staff of Asklepios, was always a mediator between worlds, a code for knowledge that burns as much as it heals. In the mythic imagination, the serpent insinuates itself. It enters the scene sideways, veiled in ambiguity, its power made all the more terrible for its discretion. It slides through the cracks of consciousness, unhurried, unconcerned with applause, awaiting the hour when the gaze is steady enough to see what was always there. When it arrives, the shock is not one of novelty, but of ancient recognition. The viewer discovers that the room in which the painting hangs is no longer ordinary; it is antechamber. The encounter ceases to be aesthetic and becomes tribulation.

III. Threshold and Consecration: Bearing the Coil’s Mark

Yet it would be a failure of reverence to “explain” the serpent, to draw it into the cold glare of analysis, to wound it with the scalpel of theory. The whole genius of the symbol lies in its capacity to withdraw, to remain partially submerged, to lure without surrender. What happens, then, when the viewer dreams of the serpent? When, in the dream, the coil encircles another beloved form, one whose features seem almost to echo those of the painted model, and yet exceed them in intimacy? Is this mere projection, or is it the serpent itself, moving through the fields of consciousness, rewriting the script of desire and memory? Such questions are less for answer than for cultivation. In those moments, the serpent’s true function becomes apparent: it is the keeper of thresholds, the guardian of all that must remain latent until the appointed hour. To bear witness to the serpent is to be marked by vocation. The coil consecrates. It sets the one who sees apart, entangling them forever in the apparatus of shadow and revelation.

Epilogue

When the hour of seeing finally arrives, it is never solitary; it brings with it the echo of all those who saw before, and all who will see after. The serpent that waited in darkness now lives, not only on the painted flesh, but in the viewer’s marrow, in their waking and their sleep. Its lesson is never exhausted; each time the gaze returns, another layer of meaning stirs beneath the scales. The painting is Mirror, passage, sentence served and delivered. In the room where the old self died, the serpent moves still, faithful to its ancient art: to appear, at last, just where the darkness had seemed unbroken. And whoever carries its mark does so quietly, with the discretion of one who knows the price and the privilege of seeing what moves in shadow.