In certain texts, reading is a ritual immersion in the mineral tides that underlie the world’s ephemeral surface. Among such works, Stoner by John Williams stands as a winter bloom in the withered field of American prose; austere, withholding, and strangely radiant in its refusal of spectacle. It resists the hunger for epiphany. Nevertheless, as in the study of ancient glyphs, patience reveals a hidden architecture; a pulse that persists beneath the frost, obeying a law that is neither visible nor declared.

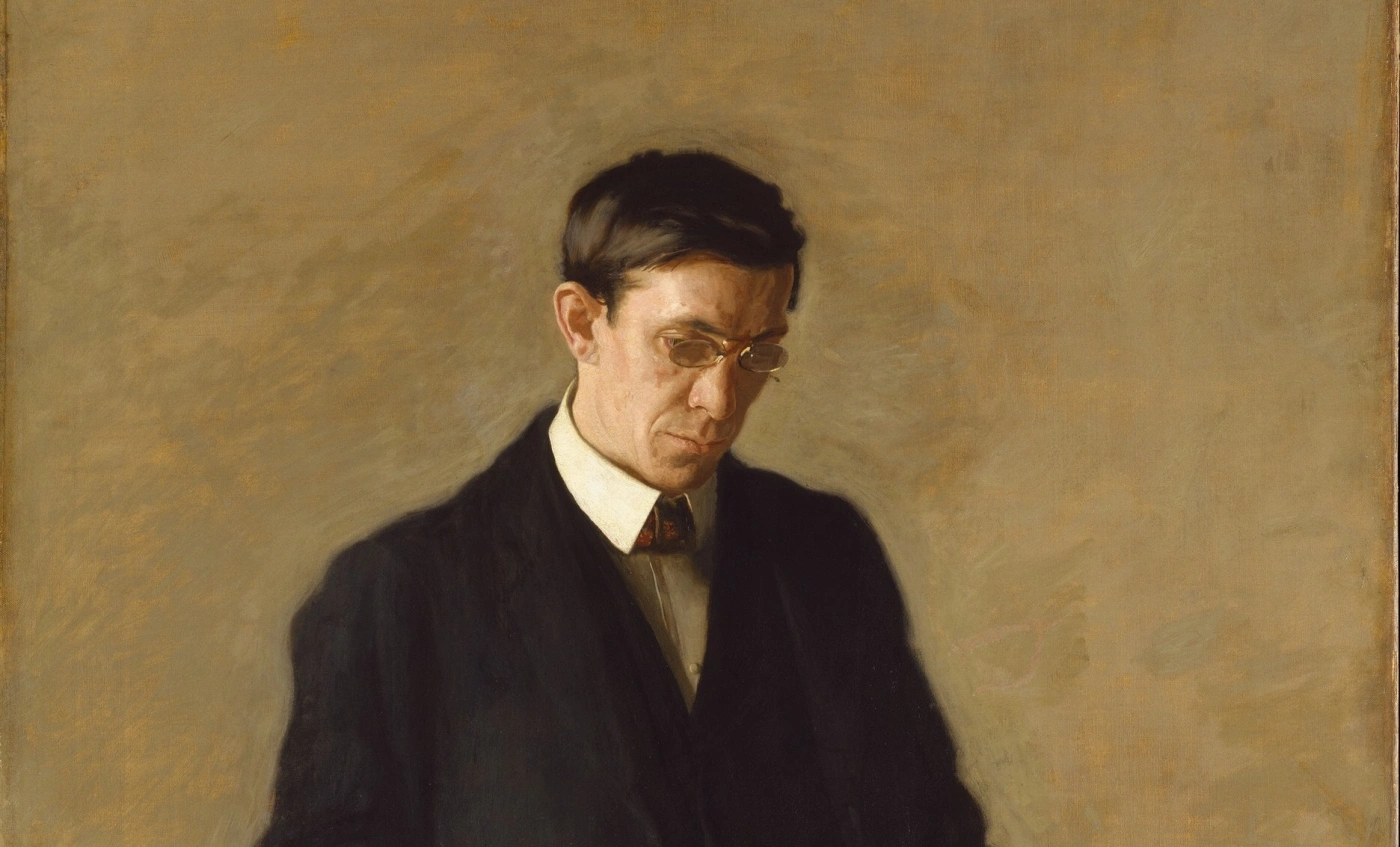

At the novel’s centre is William Stoner, so often mistaken for an apostle of mere endurance; a modern Job clad in the silence of unyielding soil. He is made to vanish beneath the layers of habit, disillusion, and humiliation; the world seems intent upon his disappearance. It becomes easy to assign him to the gallery of the vanquished. Such readings miss the soul at the heart of the silence. Stoner’s dignity belongs to a lineage more ancient than stoic resignation; he is kin to the Tzadik Nistar, the Hidden Just who, in the shadowed teaching of Kabbalah, supports the world in silence.

The legend of the Thirty-Six Just (Lamed-Vav Tzaddikim), folded within Talmudic and Zoharic night, holds that a scattered few, unknown to themselves and others, sustain the axis of mercy. These figures, whose humility is their veil, whose suffering is altar and offering, act with neither miracle nor acclaim. Their merit is weight without witness, a scaffolding beneath the seen, a lunar logic. To recognise Stoner among these is to read with the other eye, allowing his trials their veiled grandeur; grandeur of the thread that holds all things, not through noise, but by silent fidelity. Such is the lunar current that Williams invokes in the novel’s hush.

I. The Hidden Lattice of the Righteous

The image of the Just Man has haunted mystical imagination across centuries. The Babylonian Talmud, through oblique utterance, speaks of thirty-six concealed righteous upon whose merit the world’s survival rests (Sanhedrin 97b; Sukkah 45b). In the Zohar’s secretive prose, these Lamed-Vavniks remain invisible, even to themselves; humility their habit, suffering their consecrated silence. There is no miracle here, no hero’s narrative; the righteous dwell in the periphery, unnoticed, sometimes ridiculed.

This is the law of the moon; presence concealed, radiance without glare, endurance through the waxing and waning of fortune. The world is held by anonymous fidelity; by those who persist in their small acts, woven into the fabric of the invisible. Stoner emerges from these shadows; he is not a name for the chronicle nor an argument for virtue. Suffering attends him quietly, folded into the grain of old desks, into the brief gestures and vanished seasons. Through it all, an unbreakable thread endures. It is fidelity to a centre not of his own making, a vow spoken to silence itself.

II. Suffering and Fidelity: Beyond Stoicism

Some have viewed Stoner through the lens of stoicism, drawing parallels with the contemplatives of the Portico. To bear what fate decrees without complaint is praised among the wise of many traditions. Williams, however, sets his figure in a landscape more unyielding. Suffering, in Stoner, is neither the path to virtue nor a theatre of the heroic; it is the crucis through which fidelity reveals itself.

The thread of Stoner’s existence is not tied to any dogma. His vow is inward, sealed in the devotion to literature, to language, to the secret music of teaching and reading. When all else falls away, honour, companionship, even hope, this ember remains. He preserves the vow because some knowledge remains that meaning is woven into the world, though seldom named aloud. Suffering is endured, not chosen; it becomes the condition through which the vow persists.

Kabbalistic imagination sees in suffering neither mere punishment nor virtue. It is the darkened vessel in which the occult spark is kindled; the shell which, in breaking, releases what cannot perish. The Just One accepts its necessity for the world’s endurance. Stoner’s humility is a form of resistance against dissolution, a quiet refusal to betray the flame entrusted to him.

Williams refuses the reader the comfort of catharsis. No deus ex machina, no reversal, no vindication. The world remains indifferent, yet within Stoner a radiance grows, a certainty, silent and indestructible, that fidelity is its own reward. The Tzaddik is unknown and unsung, but the world leans upon him, as the hidden lattice bears the weight of the visible.

III. The Beauty that Veils Itself

In the Zohar, the Rose blooms among thorns, unfolding by moonlight, its perfume discerned by those who have learned to read in darkness. Stoner’s life is this Rose; beauty neither named nor declared, a hush that traverses the prose, glimpsed only by the other eye. Disappointment shadows the narrative, joy is muted, connections fail. Nevertheless, beneath the coldness, something persists, a knowledge that beauty endures, though denied and unspoken.

Williams shapes the novel with the tact of the artisan in darkness. The prose is a vessel, holding more than it declares; it invites, then withdraws, demanding patience. Stoner’s perception grows in quietness. He never preaches, never theorises; he lives the vow, becoming its mirror.

To stand among the Just is to be essential without witness, to persist in faithfulness despite every sign of futility. Stoner’s death is the final act of his vow; he dies as he lived, eyes open to the page, certainty unbroken. The lunar thread that winds through the novel is the rhythm of the hidden world; light that neither blinds nor deserts, beauty that survives exile.

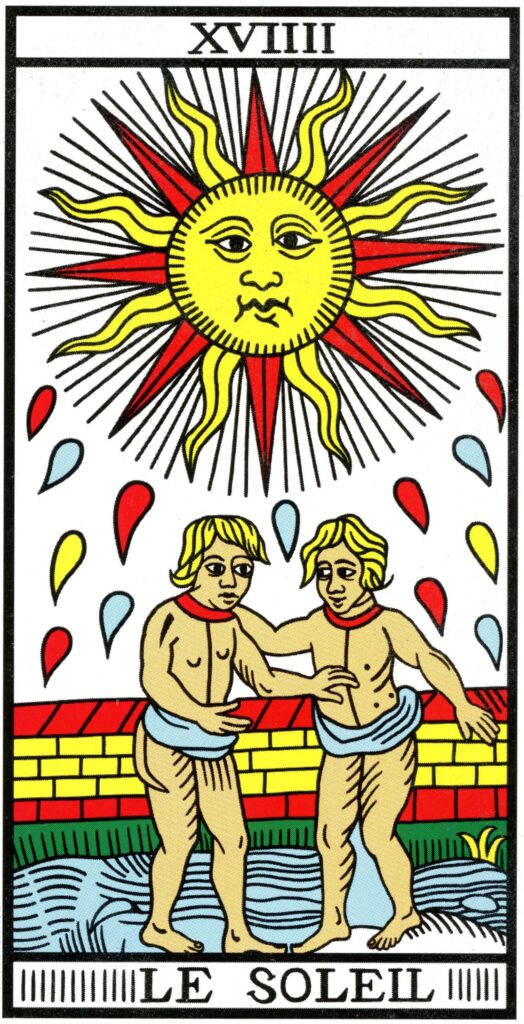

Coda: The Arcane Sun

In the secret numerology of the Major Arcana, the nineteenth portal is marked by the Sun, a mystery bound to the Hebrew letter ר (Resh) and to the path that draws a luminous current from Hod towards Yesod upon the Tree. Tradition ascribes to this passage the silent operation of clarity, a radiance passing through the vessel of the Word, seeking to incarnate in the secret architecture of life. Stoner became such a vessel. Throughout the hush of unrecorded years, the source-light never flickered in him; adversity served only to refine its gold. He remained bound to the solar root, invisible to the world’s reckonings, but entirely faithful to that which called him beyond the measures of praise or defeat. In his solitude, Resh’s silent benediction was inscribed upon him, sustaining an interior dawn when all other lights had receded.

As the story closed and the night gathered, absorption became consummation. The same fire he sheltered welcomed him, dissolving the last boundaries between guardian and source. Stoner vanished from all else’s gaze, but was received within the immensity of the solar mystery. The world remained unaware, but, within the order of the arcana, the flame endured; undiminished, immaculate, transfigured. Such is the riddle of the nineteenth path: the Sun persists through the faithful; Verbum becomes flesh; the hidden gold is never lost. The Just man departs, yet the Sun within the vessel shines on. In the silence of Hod, in the dreaming of Yesod, the seal of ר abides.

Fiat Lux.