In the dim chapel, upon marble that breathes the centuries, the script carves its wound: Tuam ipsius animam pertransibit gladius. The phrase, lifted from the Gospel according to Luke, echoes as a living sigil. This is the sword that passes through the soul, the gladius announced to Mary by the lips of the aged Simeon. A prophecy, indeed, but above all a revelation of the law that governs the birth of the Divine into flesh. It is not the flesh that is wounded first, but the soul that consents to be pierced. This sword, in its Latin precision, divides marrow from Spirit and marks not merely the mother of Christ, but all who bear the Word. Within the stone, the letter is kept alive, a silent operator for any who would contemplate its mystery. The soul that generates the Divine is called to suffer the blade; to suffer, in turn, is to embody the deeper maternity for which the Virgin becomes image and threshold.

Luke, whose gospel alone preserves these words, crafts his narrative as a physician of the secret body. His is the gospel of boundary and visitation, annunciation and exile, of the Divine hidden and revealed through veiled forms. His language, in Greek and in the Vulgate, intertwines the visible with the invisible, so that prophecy bleeds into history and history, in turn, ascends to symbol. Simeon’s utterance at the temple is not even a warning, but the unveiling of a cosmic paradox: to bring forth the Logos into the world is to accept that the soul will be wounded and, through this wound, the world is saved. Tradition, both patristic and mystical, has never ceased to tremble before this line. For the sword that passes is not a thing of steel, but the flaming blade that guards the gate of the heart; it is the necessary suffering that opens the vessel for incarnation. The verse in Luke 2:35, commented by Origen, Ambrose, and the Syrian mystics, becomes the axiom of all true theurgy: the higher the gift, the sharper the wound.

I. The Gladius and The Soul: The Logos as Sword

No mere object of violence, the sword is the axis and apparatus of discernment, the emblem of the Word itself. In the ancient world, the gladius was not only a weapon of war but a tool of separation. In the Roman rite, the sword divided sacrifice from altar, marking out that which belonged to the gods. The phrase from Luke evokes this ancient memory; the soul of Mary, archetype of the receptive vessel, is to be traversed so that the Divine can enter the world. This is echoed throughout the hermetic corpus, where the sword becomes the rhomphaia pneumatos; the blade of Spirit that divides appearances from essence.

The Epistle to the Hebrews speaks of the Word as a double-edged sword, cutting through soul and Spirit, joints and marrow, discerning the thoughts and intentions of the heart (Hebrews 4:12). This is the precise law of Spiritual operation. The Logos, in its descent, wounds the host; that which is unworthy is cast away, what is secret becomes revealed, and the one who bears the Word cannot remain unscarred. In Mary’s case, the wound is shared, silently, by all who give passage to the Divine. The Kabbalistic tradition preserves this wound as tzimtzum, the contraction that allows the Infinite to dwell in the vessel. In the Christian mystical tradition, the sword is a sign: the Divine is not born but through blood, literal or symbolic. This principle is mirrored in the texts of the Desert Fathers, who speak of the wound of love as the only proof of real theosis.

II. Marian Parallels: The Wounded Feminine

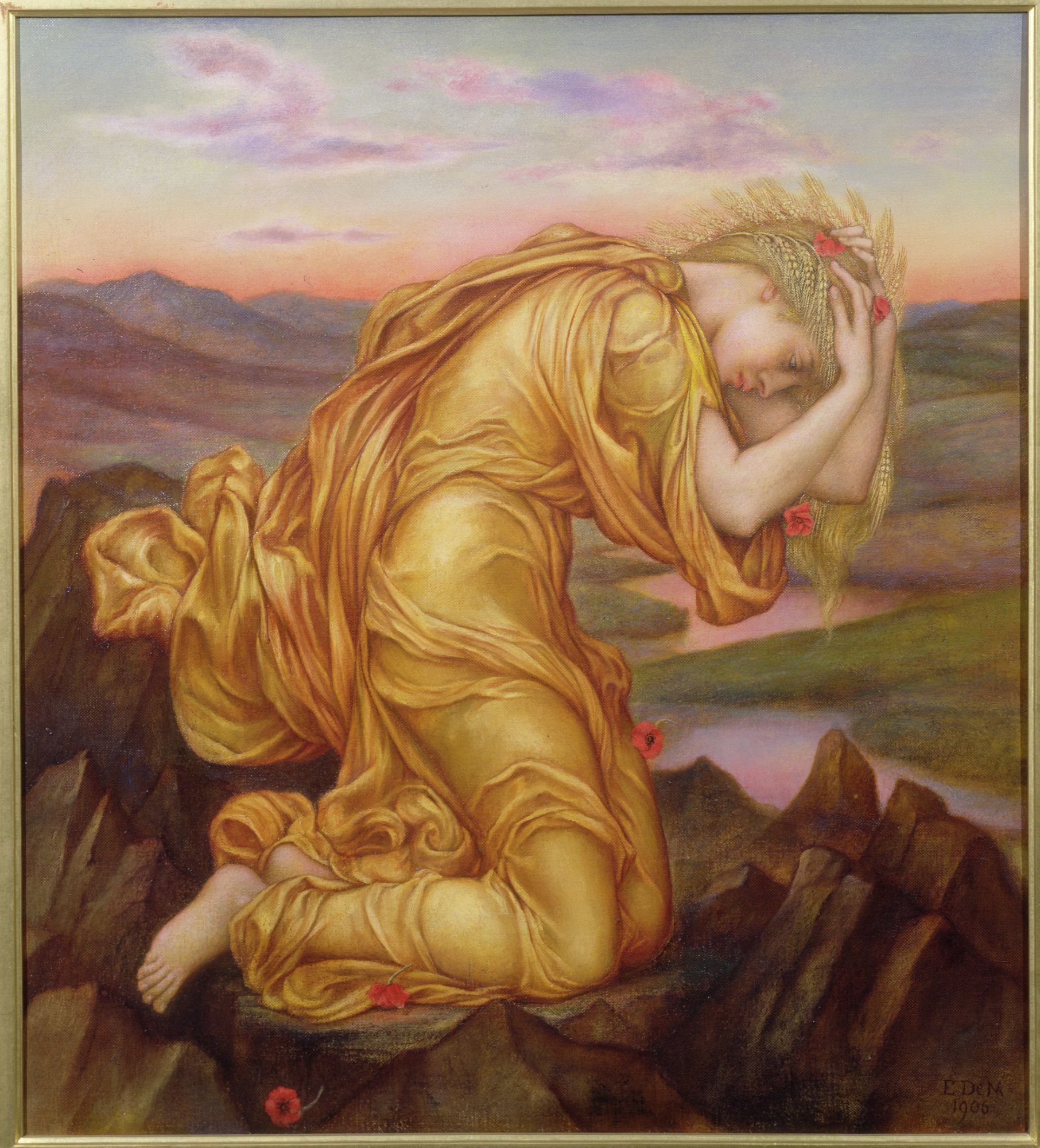

The phrase that marks Mary is not hers alone. The Sacred feminine, wherever it manifests as vessel of the higher, is always followed by pain that becomes the price of transmission. In the Egyptian corpus, Isis is the mourner and the magician, forced to wander, to gather the dismembered Osiris and to conceive through the absence that wounds her. Her lamentations are spells, her tears rivers of creation, her fidelity is a shadow of Mary’s own consent to the sword. In the Greek mysteries, Demeter suffers the abduction of her daughter; her barrenness is a curse upon the earth until the loss is recognised, her wound restored.

In the gnostic currents, Sophia is cast out from the Pleroma, her exile birthing both the cosmos and the tragedy of divine forgetfulness. Her pain is a fall whose redemption requires the passage of gnosis; gnosis that itself cuts the soul, for to know is to bleed. In the shadowed rites of Kemet, Nephthys serves at the threshold; her sorrow is the anonymity of the altar, her pain without child yet fertile in the work of resurrection. Even Coatlicue, in the world before conquest, conceives through the wound, is slain by her own offspring, and wears the serpent as necklace, with her soul transpassed by the agony of creation. In the Christian mystery, the wound of Mary is the template: the blade that passes through the soul is the seal of those who bear the Verbum, the ineffable scar of the mother, prophet, priestess, and oracle. Hildegard, Mary Magdalene, and Claire of Assisi endure the wound of seeing more than what can be spoken. The sword is never absent from the feminine that brings forth the Sacred; it is the signature of authenticity, the necessary blood-price for all incarnation of meaning.

III. The Pain That Consents: Suffering As Operative Offering

What transpires in the soul transpassed by the sword is not mere endurance, but consent: an act that elevates pain from fate to offering. Mary’s pathos at the foot of the cross is not that of a mother broken, but of a vessel remaining open. The mystical traditions have always insisted that the greatest pain is that which is accepted, embraced in lucidity and made fertile. Pain that is rejected becomes mere laceration; pain that is offered transforms itself into altar. I

In the initiatic rites, whether Eleusinian or Hermetic, the candidate is marked by tribulation. The suffering is not accidental, but a technology: it rends the fabric of the self, hollows the vessel, prepares a dwelling for the higher presence. The Persian magi called this the fravashi, the carving of the soul into a fit habitation. In Kabbalistic texts, suffering is called the sweetening of the judgements: the acceptance of the sword as the price for wisdom. The Rose blooms only where the cross has already wounded the flesh. The feminine figure who accepts the gladius is royal; she reigns in the silent fidelity to the pain that she has chosen to transmute. The liturgy of pain becomes the locus of operation, the secret whereby suffering is not only endured, but instead transformed into the very means by which the Divine is brought into the world. This is the hidden teaching of the sword: that no pathway remains whole, and that wholeness is itself found in the acceptance of division.

Coda: The Martian Boundary of the Feminine

Geburah emerges along the left-hand pillar, clothed in the red of Mars, manifesting the holy severity that forms and protects the vessel. Within the Kabbalistic tradition, Geburah’s sword is not unleashed in blind fury; it is the operation of sacred boundary, the courage to separate, to name, to defend what is worthy. This is the feminine in its uncompromising clarity: a womb that knows when to close, a veil that conceals, a flame that purifies.

Those who contemplate Geburah may sit with a solitary flame, attending to the interplay of light and shadow that emerges on the altar of their own hands. A breath may become a silent invocation, a memory of a single act of fidelity: a word withheld, a frontier kept. Let the presence of the sword be felt in restraint, not in violence, but in the silent stance of the guardian at the threshold. The Lady, robed in scarlet, stands beside the flame; she teaches by what is withheld, by what remains unsaid, by the dignity of the wound.

Within Geburah, the channel is carved, the altar guarded, the vessel dignified by its emptiness. The sword offers form, not threat.

Fiat Lux.