Omphalos (ὀμφαλός) literally means navel. However, in ancient Greek, the word carried a meaning broader than a mere anatomical organ: it designated the point of connection between the inner and the outer, the mother and the child, as well as the cosmos and its origin. When Delphi is called omphalos tēs gēs – the navel of the Earth -, it means that the entire world is nourished by an invisible cord connecting it to the Divine.

In Ezekiel 38:12, within the context of the prophecy against Gog of Magog, there is the Hebrew expression “עַל־טַבּוּר הָאָרֶץ” (‘al tabbur ha’aretz), which literally means “upon the navel of the earth.”

The term טַבּוּר (tabbur) is the exact Semitic equivalent of ὀμφαλός and both words share the same dual meaning: anatomical and cosmogonic. When Ezekiel speaks of “those who dwell at the navel of the earth,” he refers to a specific Sacred centre, the point of contact between the Divine and the terrestrial, the same concept that the Greeks expressed with the Omphalos of Delphi.

In later rabbinic tradition, this tabbur ha’aretz is identified with Zion or Jerusalem, the spiritual centre of the world, the Axis of Creation from which the breath of God expanded the Earth. The Midrash Tanchuma even says explicitly: “Just as the navel is at the centre of the body, so Jerusalem is at the centre of the world.”

The full numerical value of טבור (tabbur) is indeed 217, when each letter is counted according to its standard gematria value. This number is particularly suggestive, since 217 is also the value of the Hebrew words meaning “exactly,” “precisely,” “correctly”, expressions such as בדיוק (b’diyuq) or נכון (nakhon) in certain ancient Kabbalistic permutations, both referring to the idea of precision, rightness, and correctness.

The tabbur, the navel, is not merely the vital centre but the point of cosmic exactitude, where everything stands in perfect measure and proportion. The number 217 is the numerical seal of the rightness of the centre, the cipher of perfect correspondence between above and below.

Jules Verne’s Voyage au centre de la Terre (1864) is one of those symbolic coincidences that echo far older myths. When Professor Lidenbrock points downward and says, “Let us go down to the centre of the Earth,” he is unknowingly repeating the Delphic gesture: a descent to the Omphalos.

A man of science with an alchemical imagination, Verne re-creates in the nineteenth century the ancient Orphic descent. His “centre of the Earth” is hermetically the womb of the world, the same tabbur ha’aretz of Ezekiel, the place where the human being meets its origin. The entrance to the journey is a volcanic fissure in Iceland (a fiery navel), and the path, through tunnels and underground chambers, mirrors the initiation routes of the old temples. The traveller, while descending, approaches the vital cord of the planet, the point where matter still remembers the Divine.

The umbilical cord is also the sigil of the initiatory thread. In the mystery traditions, the rope is used to ritually reproduce the bond between the neophyte and the centre, the body and the principle that engendered it. That is why in ancient initiations, such as the Orphic or Masonic, the initiate is led with a cord around the waist, the neck, or the chest: this bond symbolises the spiritual umbilical cord that keeps him connected to the Mother of the World while he undergoes the inner birth.

At the same time, the Delphic Omphalos was covered by a net of interwoven wool, imitating that very cord: the wrapping of life, the thread of the Moirai, the web of manifestation. The Moirai (Μοῖραι), known in Latin as the Parcae, are the three goddesses of destiny, Clotho, Lachesis, and Atropos, who govern the thread of life for all beings, mortal and Divine alike.

Clotho spins the thread, Lachesis measures its length, and Atropos cuts it when the appointed time is fulfilled. They preside over their measure and duration, the just proportion that keeps the cosmos in order. The name Moirai comes from moira, meaning “part” or “portion,” and expresses the idea that each being has its allotted share of existence, a fragment of the universal fabric it must weave and bring to completion. Μοῖρα is also rooted in the same conceptual field as the Latin pars, used in Hermetic, Hellenistic and Arabic astrology, the so-called Parts or Lots, such as the Pars Fortunae and the Pars Spiritus.

The Moirai weave the thread of life under the governance of Jupiter, the Demiurgic Ordainer. He is more than the god of thunder, becoming the weaver of the cosmos, the one who measures, distributes, and maintains the proportion of all things. In the Kabbalistic Tree, Jupiter corresponds to Chesed, the first of the lower sefiroth and the emanation that opens the world beyond the Supernal Triad. It is through Chesedian Jupiter that the ordered manifestation of the cosmos begins, the descent of Divine mercy taking form as law, structure, and rhythm. In the Orphic hymns, even the Moirai act according to his will; destiny appears as a form of divine arithmetic.

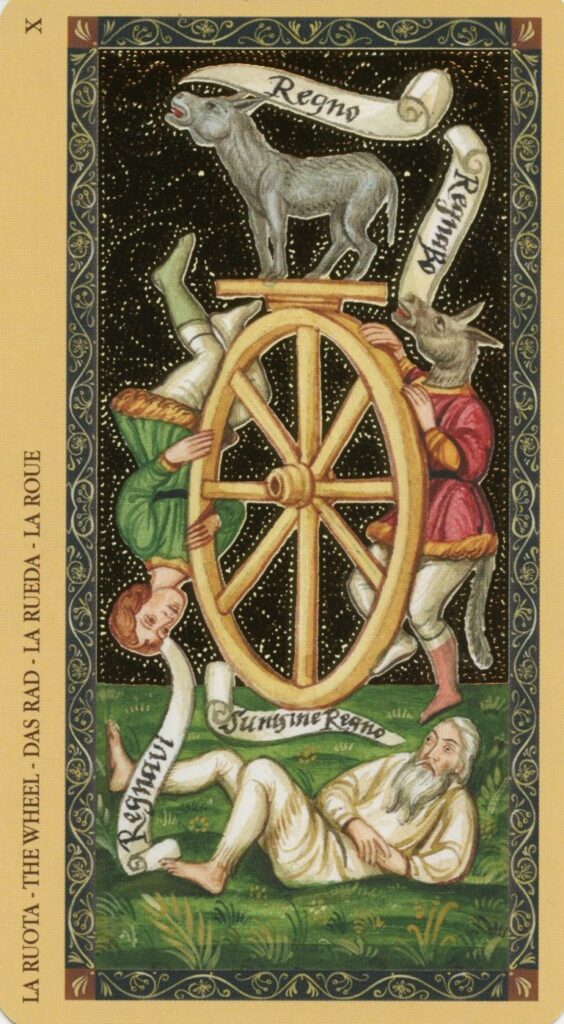

In the Tarot, this same principle is revealed through Arcana X, the Wheel of Fortune, the card consecrated to Jupiter as the cosmic ordering intelligence. The destiny of the Moirai becomes visible motion: the Wheel turns while its centre remains still, like the Omphalos of Delphi. The number of the card is 10 and it completes the Pythagorean 1+2+3+4, the Tetractys, symbol of manifested totality and of the completed cycle. The number four embodied in the Tetractys corresponds to the kosmos, a Greek word (κόσμος) whose original meaning is far more profound than mere “universe.” Derived from the verb κοσμέω (kosmeō), meaning “to arrange, to order, to adorn,” meaning the ordered beauty of creation, the harmonious disposition of all things according to measure. Hence the kosmos is the manifestation of Divine order, the visible reflection of the intelligence that sustains the world in proportion and symmetry. And Chesed is also the sephirah number four.

Jupiter, as Zeus, repeats the primordial gesture when he releases the two Eagles, one towards the East and the other towards the West, so that they may meet at the centre of the Earth, the act that gives birth to the Omphalos, marking the reconciliation of opposites. The union of these two currents allow the centre to be revealed, since the convergence of East and West mirrors the eternal marriage of Sun and Moon, Spirit and soul, gold and silver. The Omphalos is the fruit of this conjunction, the fixed point where light and reflection coincide.

The Delphic tradition also expresses this alliance throughout its symbolic structure. The sanctuary of the Omphalos, Delphos was consecrated to Apollo, the solar god of measure and harmony, but his voice was transmitted through the Pythia, the lunar priestess who spoke in trance under the breath of the Earth. The centre of Delphi was the place where Apollo and the Pythia met, Sun and Moon, reason and inspiration.

From this symbolic union also derives the figure of Janus, heir to the gesture of the Eagles and guardian of the same mystery. The two-faced god gazes simultaneously toward East and West, day and night, the visible and the hidden. He is the initiatory interpreter of both worlds, the one who understands at once the exoteric and the esoteric ways.

This same symbol continues in the Byzantine double-headed Eagle. Historically, the double head of the imperial Eagle appeared in Late Antiquity, being adopted by the Byzantine Empire as a dynastic emblem in the thirteenth century, particularly under the Palaeologi. It represented the simultaneous sovereignty over East and West, Constantinople’s claim to be the continuation of Rome. But this double vision already existed within the Hellenic imagination: in Zeus, lord of the Eagles, and in the founding of Delphi, where the two birds marked the world’s central point. Christian symbolism inherited this cosmic archetype and gave it political form.

From an esoteric and hermetic point of view, the reading is even deeper. The double-headed Eagle embodies the dual solar and lunar principle, the same that united Apollo and the Pythia at Delphi, and Janus in his two faces. One head looks toward the rising Sun, the other toward the setting Sun: both share the same body, the same Spirit, the same axis, like the initiate who learns to see the visible and the invisible while remaining centred.

This symbolism was preserved and transmuted in Freemasonry, especially within the Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite, where the crowned double-headed Eagle expresses the sovereign consciousness that governs the two natures of being, terrestrial and celestial. The inscription accompanying it, Deus meumque jus, encapsulates the same truth: the inner centre, the spiritual Omphalos, as the point of union between East and West, Sun and Moon.

The emblem itself was formally adopted from the personal standard of Frederick II of Prussia, known as Frederick the Great, initiated into Freemasonry in 1738 and regarded as a bridge between the Enlightenment and the Hermetic Tradition. According to Masonic tradition, he sanctioned in 1786 the so-called Constitutions of Frederick, which defined the structure of the thirty-three degrees and established the principle of the Supreme Council, whose seal became precisely the double-headed Eagle.

In adopting and disseminating the motto “Gott mit uns”, Frederick re-inscribed on the political plane what in Isaiah 7:14 had been a mystical prophecy: “Behold, a virgin shall conceive and bear a son, and shall call his name Emmanuel” — that is, “God with us.” The Prussian device, engraved on the soldiers’ belt buckles and banners, projected outward the same principle that, on the initiatory plane, is internalised in Deus meumque jus.

Kύριε ελέησον