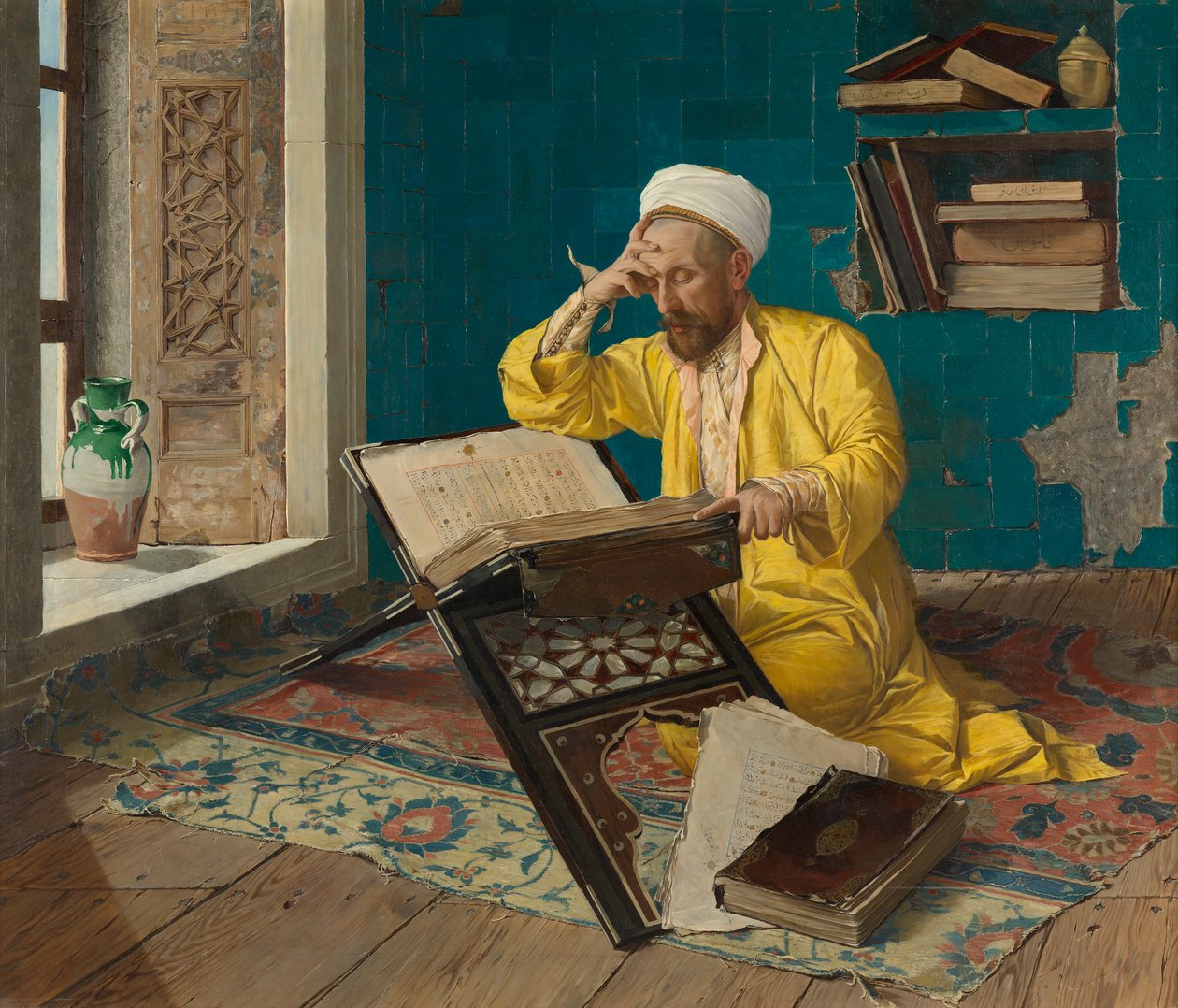

I was just reading John Michael Greer on discursive meditation, understood as a process that exercises the capacity to work with symbols in an intelligible way, a deliberate training of the symbolic muscle through repetition. Meditation has always been this, before its modern reduction to the exact opposite, the idea that meditating means emptying the mind. The word itself says something else. Meditation comes from the Latin meditatio, from meditari, which means to think at length, to reflect, to ponder, to rehearse inwardly. It is linked to the Indo-European root med-, associated with measuring, caring, considering. Nothing here points to emptiness. It points to rumination, to the act of chewing the same content again and again until its juice is extracted.

That is precisely why, in monastic practices, so much emphasis is placed on repetition and on Lectio Divina. What matters is not the mere historical or theological understanding of Scripture, but what the scene, the image, the phrase provoke within, in the organ of the imagination. This work is done through the ruminative repetition of psalmody, continuous recitation, the sustained presence of the image in the mind. The same principle lies behind the contemplation of the Tarot for those who practise cartomancy, or behind the incessant repetition of the Kyrie eleison on Mount Athos. In all these cases, symbols function as keys. Not so much to “explain” something, but to open, or at least to give form to, the inner imaginative world of the human being.

In recent weeks, I have been reflecting insistently on a statement by Christ in the Gospel of John, when He speaks of the “prince of this world”. The usual translation as prince is poor. The Greek text uses the word archōn (ἄρχων), which means ruler, regent, one who exercises authority. It comes from the verb archein, to govern, to command, to initiate. It is the same term that would later give rise to the Gnostic notion of the archons, the rulers of the lower cosmos, often described as the jailers of incarnation. The term itself suggests a cold, structural, almost mechanical form of regency, tied to the order of the world as it functions in time and space, an order that repeats itself, that administers, that controls, that punishes.

The inevitable question from meditation then arises: who is this Archon? The automatic answer points to Satan, the adversary. But that answer, if it stops there, is of little use. Where is this Satan? Where can he be identified, concretely, in everyday life and within ourselves? There is no need to fall into catechetical frenzy, or to project the diabolical onto others, as if evil were always somewhere outside, embodied in grotesque figures ready to be denounced. If the Archon is the ruler of this world, and if the condition of the world is indeed despotic (and it is), then it matters to understand where and how that despotism is exercised. Reducing it to mediocre politicians or visible figures of power is a comfortable simplification, but an insufficient one.

The Archon governs everything that functions by automatism, everything that repeats itself without consciousness, everything that turns life into a closed circuit of punishment, guilt, and mechanical reaction. He governs the processes that crush us through blind repetition, the habits that harden, the inner mechanisms that judge, punish, and restrict. And this is not only “out there”. Those same devices exist within us. There is an inner archōn always ready to administer, to correct, to tighten the noose, to reduce life to a set of predictable gestures and conditioned responses.

When Christ says, “Now is the judgment of this world; now shall the prince of this world be cast out” (John 12:31), or again, “The prince of this world is coming, and he has nothing in me” (John 14:30), a fundamental division is established. Christ is in the world, but He is not of the world. “They are not of the world, just as I am not of the world” (John 17:16). The distinction opens between being and being-in, between a transient condition and substance. What Aristotle would call ousía, essential and immutable substance, as opposed to passing states. It is the same intuition that, in other languages, appears as the Gnostic divine spark or as the spark of Light, known as nitzotzot (נִיצוֹצוֹת), spoken of by the Kabbalists.

The Logos enters time without being absorbed by it. “And the Logos became flesh and dwelt among us” (John 1:14). The Light enters the darkness, but is not dissolved by it. “The Light shines in the darkness, and the darkness did not overcome it” (John 1:5). The Logos accepts to be born and to die in the flesh, like the Sun that rises and sets every day, but its ousía remains intact. The Resurrection then emerges as the supreme symbol of that permanence, the final victory over the regency of the archōn of this world, whose principal instruments are time and space, the conditions that subject bodily life to limit and to death.

This is just an example of how a single verse can open the doors of discursive meditation. Attentive repetition, slow mastication, willingness to let the symbol work inwardly. And, like with all powerful symbols, it never stops to unfurl more and more.

Kύριε ελέησον