Night leans over the garden; dawn delays behind a horizon of stone. Within the hush that veils the tomb, a figure pauses, unadorned by myth and yet unclaimed by history. Her hands carry myrrh, her eyes the ache of having seen what is forbidden to name. It is she whom the scriptures conceal and, yet, in their secret folds, refuse to forget. Mary Magdalene: the forgotten Rose, the bearer of keys unspeakable, the mirror of Sophia for those who dare look sideways at the Gospels. She stands among those selected by the Word itself when language turned to glyph and speech became secret again.

In the canonical imagination, she lingers on the margins; however, within the apocryphal labyrinth, her trace deepens, becoming a root that cracks the foundations of authorised tradition. The garden, always a cipher, always an elsewhere, is the stage upon which her drama unfolds. Within this space, Christ vanishes into gardener, voice dissolves into gesture. When the Logos receded, leaving the outer realm in noise, Mary Magdalene remained alone in the threshold, hearing what was left behind in silence. Her hour is not that of the spectacle; her sign is lunar, sidereal, and her language is always a shade beyond the literal. On this day, the twenty-second of July, the calendar itself marks her presence. The threshold breathes with her name, and the garden, once again, flowers under her veiled eyes.

I. The Wanderer and the Veiled Verbum

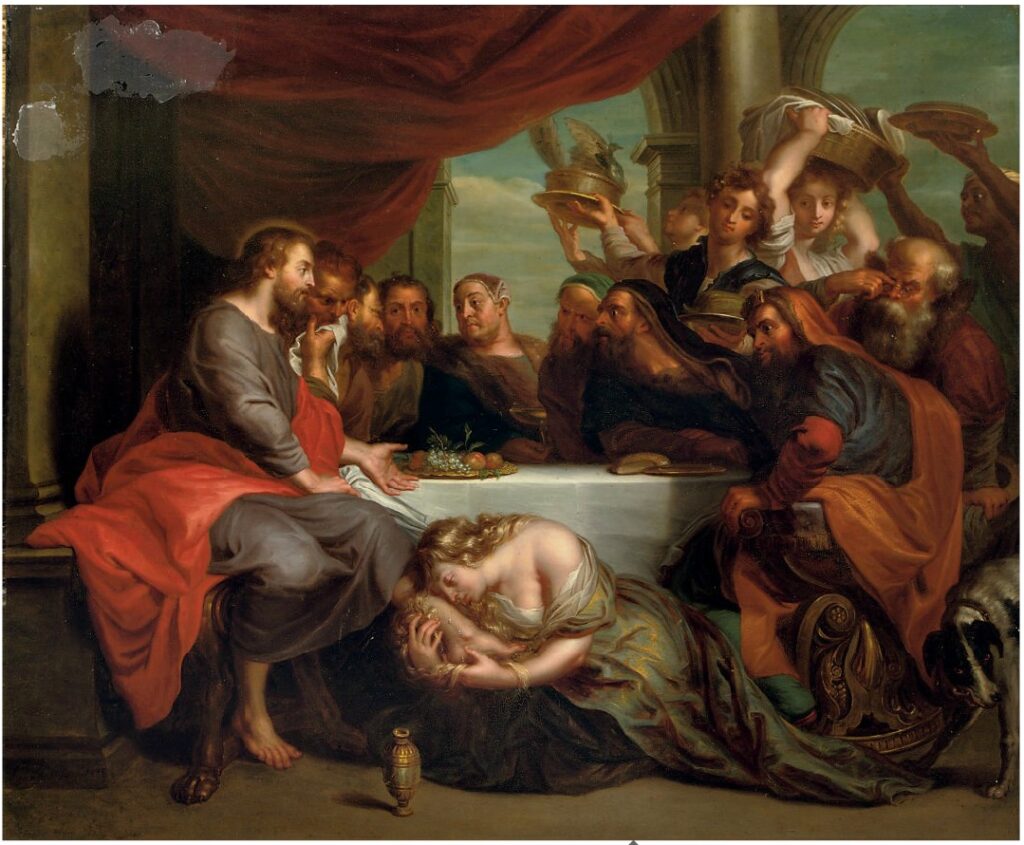

The Gnostic texts preserved at Nag Hammadi breathe the air of thresholds. They are intimate, elliptical, requiring a patient ear. In these manuscripts, Mary Magdalene emerges not as a mere disciple, but as the one attuned to the Logos once He relinquishes plain speech. She occupies a role refused by ecclesiastical rank, but anointed by the mystery itself. In Pistis Sophia, her questions outnumber all others; she alone persists when the others turn restive, even hostile. In the Gospel of Mary, her knowledge commands attention and, in its echo, resentment. “Tell us, Mary, the words of the Saviour that you know and we do not,” the text demands, revealing her distinction through the very anxiety it provokes.

Her vocation withdraws from the sentimental. Hers is the office of psychopomp, shepherdess of lost sparks, midwife to souls wandering between clay and the Pleroma. Her listening embodies the living continuity of the secret. Where Peter rails and recoils, she asks, she remembers, she repeats the Verbum through the flesh of her memory. The Master, turning inward, entrusts to her the arcane syllables reserved for the few. The veiled Word, never spoken in the squares, survives in her body as silent gnosis.

Mary Magdalene belongs to the cohort of those who descend and return. She embodies the oldest gesture: like Persephone, Inanna, Isis, she descends into absence, fragmentation, death and forgetting, only to arise with a signet not meant for daylight. Every initiatic tradition clothes its chosen with descent; she wears it with ritual dignity. Where others seek to escape, she listens to the darkness, passing through the seven gates of the underworld. At each threshold, Inanna strips away an adornment, approaching truth in the slow unrobing of the soul. But Magdalene does not strip the veils. She restores them, clothing the dead with memory, making the world once again worthy of the Word.

II. The Arcontic Siege and the Secret of Names

Among the hidden gospels, none is more dramatic than the ascent of the soul confronted by the Archons. In the Gospel of Mary, the narrative crystallises into a sequence of cosmic interrogations: after death, the soul rises only to find itself blocked by seven guardians, each embodying a layer of illusion: desire, ignorance, passion, wrath, arrogance, judgement, and finally, the sentinel of forgetting. Each one utters an accusation, binding the soul in the mesh of the created order. The voice of the Archon accuses, diminishes, compels surrender. Yet the soul answers, equipped not with weapons, but with the power of naming: “I saw you. You did not see me nor did you know me. You (mis)took the garment (I wore) for my (true) self. And you did not recognize me.”

This utterance forms the heart of the mystery. To name truly is to unmask, to annul the false claim of authority. As psychopomp, Mary Magdalene teaches this language of release. She remembers the true Names, the syllables that pierce the membrane of illusion. The planets, stripped of their luminous speech, become mere seals of clay; the sevenfold circle, a chain until the Word is spoken through the key of truth. In her teaching, the soul discovers the difference between submission to fate and the power to move through the stars without becoming their captive.

Each Archon is more than a metaphysical obstacle. The number seven is never arbitrary: it maps the planetary order, the layers of the astral body, the zones of passion and trial. Each expulsion, each exorcism, is a gesture of breaking a seal. The seven demons driven from Mary (Luke 8:2) serve not to mark her as impure, but to reveal her as one who has crossed every gate and returned. To expel is to open; to open is to climb. The zodiac ceases to be a prison, becoming instead the text she reads and liberates. Her victory lies not in destruction, but in the capacity to pass through, duly untouched, unbound, returning the world its redeemed shadow.

III. The Rose, the Seven, and the Climbing of the Soul

In the symbolic lexicon of the Mysteries, the path of ascent requires a vehicle. For Mary Magdalene, the Rose supplies the image – its petals, its wound, its perfume, and its silence. The number seven, again, reigns supreme. In Kabbalistic architecture, seven belongs to Netzach, the sphere of Venus, ruling over love, art, and the movement of desire. This Venus is never passive. She is the warrior, she is Stella Maris, the Lady of the Seven Veils. To pass through Netzach is to confront the shadow of longing, the seduction of images, the sweet poison of memory. On the Tree of Life, Netzach stands as the first sphere on the right pillar; it receives the impulse of force, balancing the rigour of Geburah.

But, in this stage, Venus is still tainted by the dream of herself. Desire clings to its forms, voice echoes in song, the mirror still shivers with old illusions. Mary Magdalene at the tomb is Netzach: longing, remembering, singing. But her passage draws her up the ladder, toward Binah, the dark sea of wisdom, where desire matures into understanding, and love takes the shape of redemption. The Rose that bleeds on the thorn of seven becomes, through her, the Rose that opens to eight: the infinity of Sophia, the Woman crowned with twelve stars in the Apocalypse, the wisdom of one who has died and returned.

Within the Gospel of John, a cipher reveals itself. After the resurrection, the disciples cast their nets and catch 153 fishes (John 21:11). This number, discussed from the Church Fathers to the Neoplatonists, signifies plenitude, the gathering of all lost fragments, the rounding of the soul. It carries further resonance: in Greek isopsephy, the name Μαγδαληνή yields 153. Such a sum declares the hidden presence, the silent totality. In the twilight of the gospel, amid the hush of the new dawn, the occulted name returns. No longer penitential, no longer stained, she rises as Sophia incarnate, the wisdom enfleshed and restored to the world through the body of her Name.

Coda: The Solar Threshold and the Recovered Garden

Twilight gathers itself over the garden, weaving silence into the very air. The world, heavy with the dust of its own forgetfulness, lingers uncertain at a liminal crossing where memory leans into hope. In the hush between veils, a single rose awakens, waiting for the soul willing to pass slowly, eyes softened, heart without haste. The garden, the geometry of all beginnings, endures, refusing to vanish, refusing to be reduced to legend. Beneath overgrowth, an unbroken symmetry persists and, beneath thorns, the perfume remains for those able to breathe without fear.

In the hour consecrated to her, Mary Magdalene does not restore a lost paradise. She recognises the living root beneath apparent decay, calls forth the garden in the heart, invoking its presence with a Word that blazes in silence. Most see only ruins and tangled stone; the discerning spirit perceives a hidden design, a fragrance that testifies. In this sacred space, drama unfolds as rite: Christ, veiled as gardener, moves through shadow, tending each gesture, sealing each threshold with care. What is offered is a glance, a whisper, a flicker of perfume marking the liminal as sacred.

Mary, keeper of memory, returns neither to what once was nor to what could have been. She renders the present transparent to myth, plants the realisation that paradise breathes wherever vigilance and reverence for the Name reside, wherever silence guards the opening of the Rose. To dwell in the garden means risking the wound, greeting the veils as invitations, accepting the burden of naming what the world would prefer to leave unspoken. One knows the gate by the quality of silence that surrounds it; the profane pass through untouched, the garden unseen.

Fiat Lux.