Time in apparitions is not linear but vertical. Between Nut and Mary, between pyramids and churches, runs the invisible thread of the Lady, the primordial Mother, Queen of Heaven, Mistress of the Womb and Abyss. In Coptic Egypt, where traditions do not die but only change names, Mary inherits the insignias of Nut: crown of stars, blue veil, sidereal womb, protective arms outstretched above the world. Nothing is new under Nut’s sky. All that appears separate repeats itself. The association between Nut and Mary is not the consequence of chance nor of modern speculation; it is the fruit of millennial layers, sedimented in myths, rites, and iconographies. To understand it, one must cross history with liturgy, symbol with body, desert with temple.

I – Nut, Lady of Heaven, Womb of Stars

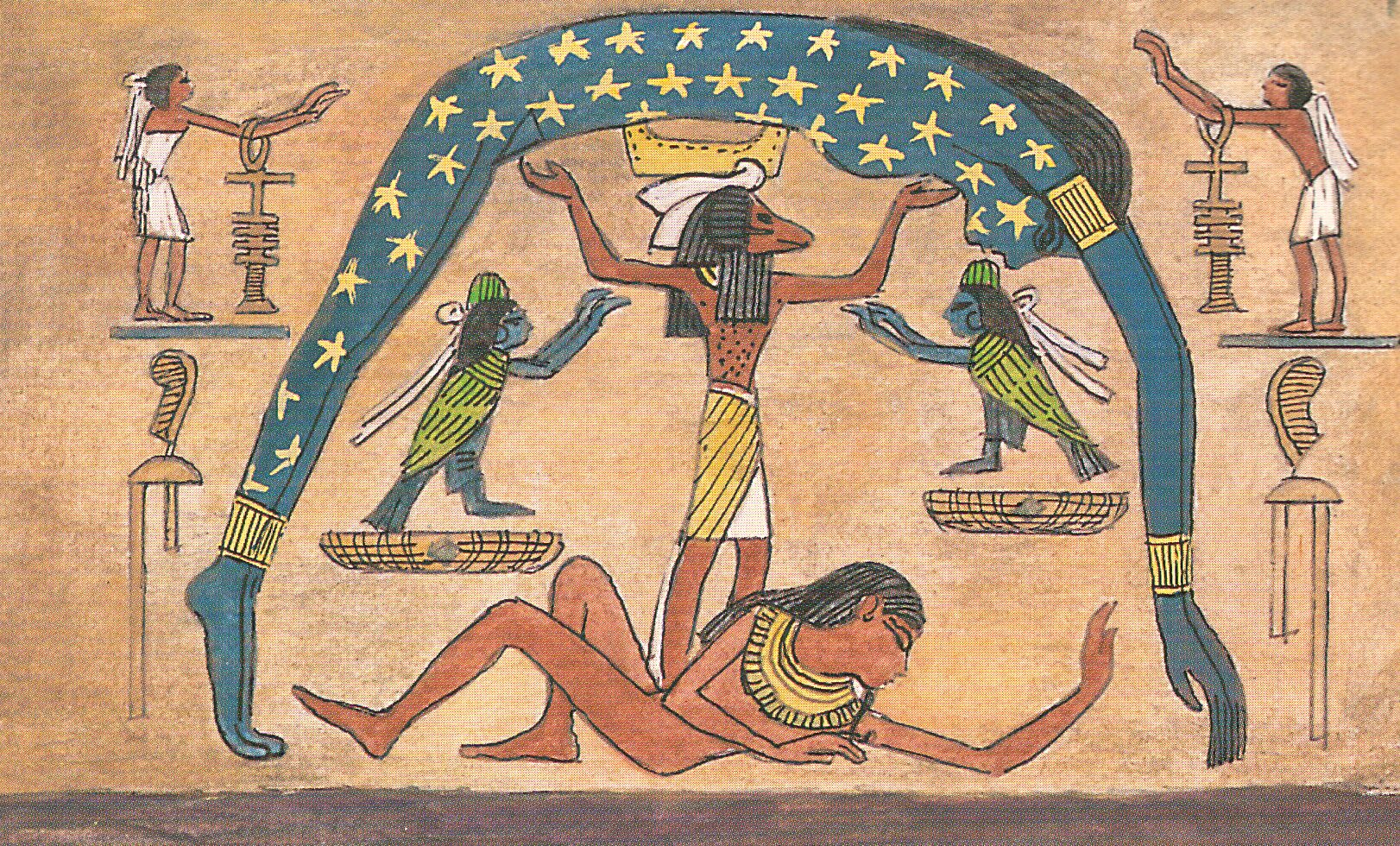

Within the Egyptian pantheon, Nut is more than a goddess: She is the sky itself. The Pyramid Texts say that, at nightfall, Nut arches her deep blue body, speckled with stars, above the earth, forming the celestial vault. Beneath her belly passes the solar barque of Ra; each night She swallows the Sun, giving him birth anew each dawn. She is also depicted with outstretched arms, fingers and toes touching the four corners of the world, Her body the boundary between order and chaos. In funerary papyri, Nut receives the deceased into Her embrace; Her image is painted on the lids of sarcophagi, promising rebirth.

For Egyptians, to die is to be received back into Nut, to await regeneration in Her night. She is the abyss and the promise of resurrection; her “milk” nourishes souls in the Duat (the afterlife), being invoked by priests, mothers, and kings. She is a sky who remembers, who covers, who gives.

II – Mary, Lady of Heavens in Egypt

With the coming of Christianity to Egypt, Nut’s ancient cult did not disappear; it was transfigured. Mary enters the land of the pharaohs as Theotokos, God-bearer, but soon wears the insignia of the local Lady. In Coptic tradition, Mary is not only the Mother of Jesus but Queen of the Heavens, Star-crowned, Intercessor of souls, Guardian of the cycles between death and rebirth.

Iconography multiplies: Mary cloaked in celestial blue, arms open wide above the world, stars upon her veil. In countless wall paintings and icons, Mary is portrayed arching protectively over the faithful, echoing Nut’s posture. Sometimes, she is depicted in “orans” position (arms uplifted in prayer), a posture identical to that found in ancient Egyptian reliefs of Nut.

III – Ritual, Symbol and Liturgical Correspondence

The parallels run deeper than iconography. Nut swallows and births the Sun, while Mary is the Mother of the “Just Sun,” Christ, “Light of the World.” Nut receives the dead to guarantee resurrection, whereas Mary, in Coptic rite, is invoked at funerals, asked to receive souls and escort them to Paradise.

Egyptian feasts once marked Nut’s epagomenal days, “out of time” days, when gods were born. Many Marian feasts in Egypt (such as the Dormition and Nativity of the Virgin) coincide with these, marked by processions, singing, and the blessing of water, all echoing the ancient rites to Nut.

In both cases, the Mother’s womb is never passive; it is an operative matrix, an abyss from which creation emerges. Egyptian women, for centuries, placed blue cloths over sick children, invoking Nut, a custom absorbed into Marian devotion, where Mary’s blue mantle “covers” the sick, the lost, and the hopeful.

Processions with candles, circles of salt or wheat, nocturnal vigils, all these belong to both the Marian and ancient cults, and are still enacted in Coptic rural festivals today.

IV – Temples, Shrines and Local Devotions

Many Coptic churches stand on sites once dedicated to Nut, Isis, or Hathor. The Monastery of Abu Serga, in Cairo, is built above an ancient sanctuary, its crypt believed to shelter Mary, Joseph, and Jesus during the Flight into Egypt. The well beneath the altar – said to have provided water for the Holy Family – echoes Nut’s association with the waters of creation and renewal. Elsewhere, at Deir el-Muharraq, a Marian shrine is built on the ruins of a temple to Nut; here, the annual Marian festival includes ritual bathing in sacred springs, processions with blue banners, and the singing of ancient litanies that blend Christian and pre-Christian invocations.

It is no coincidence that, in the Egyptian countryside, the appearance of Mary (especially in times of drought or plague) is accompanied by rituals identical to those for Nut: pouring water on the ground, circling the fields, lifting children up to the “sky” for blessing. The Lady remains the same, whatever the name.

V – Symbolic and Archaeological Echoes

Nut is painted on the ceilings of tombs and churches alike, stretching above as a cosmic dome. In Coptic iconography, Mary is often shown against a blue or golden background scattered with stars, her mantle a literal vault of heaven.

Amulets found in late antique graves in Egypt bear inscriptions calling upon “The Lady of Heaven” for protection; some merge Nut’s name with early Christian prayers to the Virgin. Egyptological studies note the parallel between Nut’s ancient epithet, “She Who Embraces the Earth,” and the widespread Coptic Marian title, “She Who Covers All.”

In rituals for childbirth, both in pharaonic and Coptic times, prayers are spoken over bowls of water, seeking the blessing of “She Who Opens the Womb.” Even the “milk of Nut” becomes Marian in some spells, invoked for nourishment and healing.

VI – Archetypal Function and the Living Symbol

At the archetypal level, Nut and Mary perform the same work: both are the passage between visible and invisible, between birth and death, between time and eternity. Both are the gate and the bridge; both shelter, generate, protect, and above all, transform. In dreams and visions, Egyptian women report seeing a Lady of Light, sometimes with the face of Mary, sometimes crowned in stars, always promising rebirth. The Christian Coptic tradition did not erase the old ways but crowned them anew. Mary did not come to replace Nut, but to give her a new name, new language, and a new story, all without betraying the original symbol.

VII – The Oracle in the Mirror

Nut and Mary arise as twin revelations of the same mystery. The former arches above the world, Her belly promising return; whereas the latter spreads Her arms, wearing the blue of celestial waters, offering protection at the edge of the unknown. For the faithful, Egyptian or universal, they offer not mere comfort but deep instruction: every birth requires a journey through the abyss, every light passes through the cosmic womb, every wound finds, in the Lady, its altar and medicine.

This association is not academic curiosity but a call to reintegrate the living symbol: to recognise in the Mother of Heaven the primordial source, guardian of cycles, Lady who never abandons the world, only changes face and name.

VIII – Final Oracle

In the Coptic-Egyptian context, Nut and Mary are the same womb working beneath different names. Every prayer to the Lady is invocation of the primordial night, a plea for rebirth, a yearning for shelter in chaos. Egypt, land of survivals, teaches that nothing dies; all is transformed. Whoever contemplates Nut, or Mary, learns to cross their own deserts knowing that, above all, there is always a Mother (arch, star, mantle) promising that the end is foreer a beginning, and that the sky, however distant, is also womb and home.