Mankind has always raised temples toward that first and unseen Light. The Egyptian city of Heliopolis, or Iunu, the City of the Sun, stands among the most ancient and exalted sanctuaries of metaphysical thought; a site where granite and papyrus converge, and the intellect dares to trace the contours of the World’s beginning. If Memphis gave Egypt its body and Thebes its heart, Heliopolis bequeathed its soul: a soul written in rays and mirrored in every subsequent doctrine of emanation.

Among the star-lit philosophies of Alexandria and the midnight lucubrations of Arab and Latin astrologers, the myth of Heliopolis persisted as a cornerstone, the very primordial pattern from which the zodiacal clock, the Sephirotic tree, and the Hermetic ladder would ascend. Each stone of Heliopolis bore a name; each pillar spoke in silence of the first act, the contraction and unfolding, whereby the Unseen reveals its veiled multiplicity. Within this perennial dawn, one glimpses the pulse that animates every later myth: the thirst for a unity beyond division, and for a source that both encloses and exceeds all forms.

One must open the Gates of Heliopolis not as an idle antiquarian, but as heir of a wisdom whose roots touch every continent and whose branches sustain the golden fruit of the Spirit.

I. The Primordial Contraction: Atum and the Nun

In the beginning, as taught by the priests of Iunu and inscribed upon the walls of Ra’s sanctuary, all was Nun, the boundless, undifferentiated ocean; a field of infinite potential, void of form, name, or Light. The Nun is both substance and absence; the eternal night from which all possibility stirs. Within its silent flood, no motion breaks the surface; no measure, no time, no god.

Out of this unfathomable depth emerges Atum; the “All-complete,” the ungenerated generator, who stands alone as the living paradox, self-begotten, self-named, self-enclosed. Atum does not fashion the world from nothing; he becomes the axis of contraction, gathering the infinite into a point, a “primeval hill” or benben that rises from the watery abyss. The sacred texts call this the “first occasion” (zep tepi): a primordial awakening in which the One becomes self-aware and, in that contraction, kindles the possibility of manifestation.

The gesture of Atum, variously interpreted by classical authors as self-engendering by Word, breath, or more physical emission, is not mere metaphor. It is a code for the act of creation by withdrawal, the self-limiting that permits all subsequent forms. In this, Heliopolis anticipates the later doctrines of tzimtzum in Kabbalah, where the divine contracts to allow the world; it echoes the Neoplatonic One, which emanates the Nous not by diminution, but by overflow within constraint.

Atum’s solitary act begets the first polarity: Shu (Air) and Tefnut (Moisture), the twin children, issue forth as principles. The cosmos does not appear fully-formed; it unfurls in sequence, each pair a mirror, each generation a deeper stratification of the primal unity. The city of the Sun proclaims a truth later echoed by Proclus and Ibn Arabi alike: the One is never lost in the Many; the Many perpetually yearn for reunion with the One.

II. The Separation of Heaven and Earth: The Work of the Demiurge

The children of Atum, Shu and Tefnut, embody the first axis of differentiation, i.e., breath and water, space and condensation. From their union arise Geb (the Earth) and Nut (the Sky), a further deepening of the dual principle. Unlike the Greek cosmogony, where Gaia lies beneath and Uranus above, Egyptian myth grants masculinity to the Earth and femininity to the Sky; a profound inversion, bespeaking a vision where fruitfulness springs upward, and the heavens are a mother’s vast, enfolding arms.

Initially, Geb and Nut are united, locked in an embrace so complete that no thing moves between them. Atum, by the agency of Shu, imposes a separation; the sky is lifted, the earth pressed down, and the space in which creation may unfold is established. This is not an act of violence, but it is the ritual opening of the world, the first architecture; what the medieval astrologers would call the templum, by which time and matter receive their dimensions. The division is generative; only by the distinction of above and below does the drama of history commence.

In the Book of the Dead, this separation is re-enacted in every sunrise, every dawn. The microcosm follows the macrocosm; every birth, every creative act requires the opening of space within the undivided. Shu, the god of air, is the archetype of mediation: the column that holds apart, the breath that animates, the priestly act of establishing a sanctuary. In the Hermetic and Kabbalistic traditions, this movement finds its parallel in the descent of Spirit into matter, in the crossing of the abyss, in the balancing of opposites.

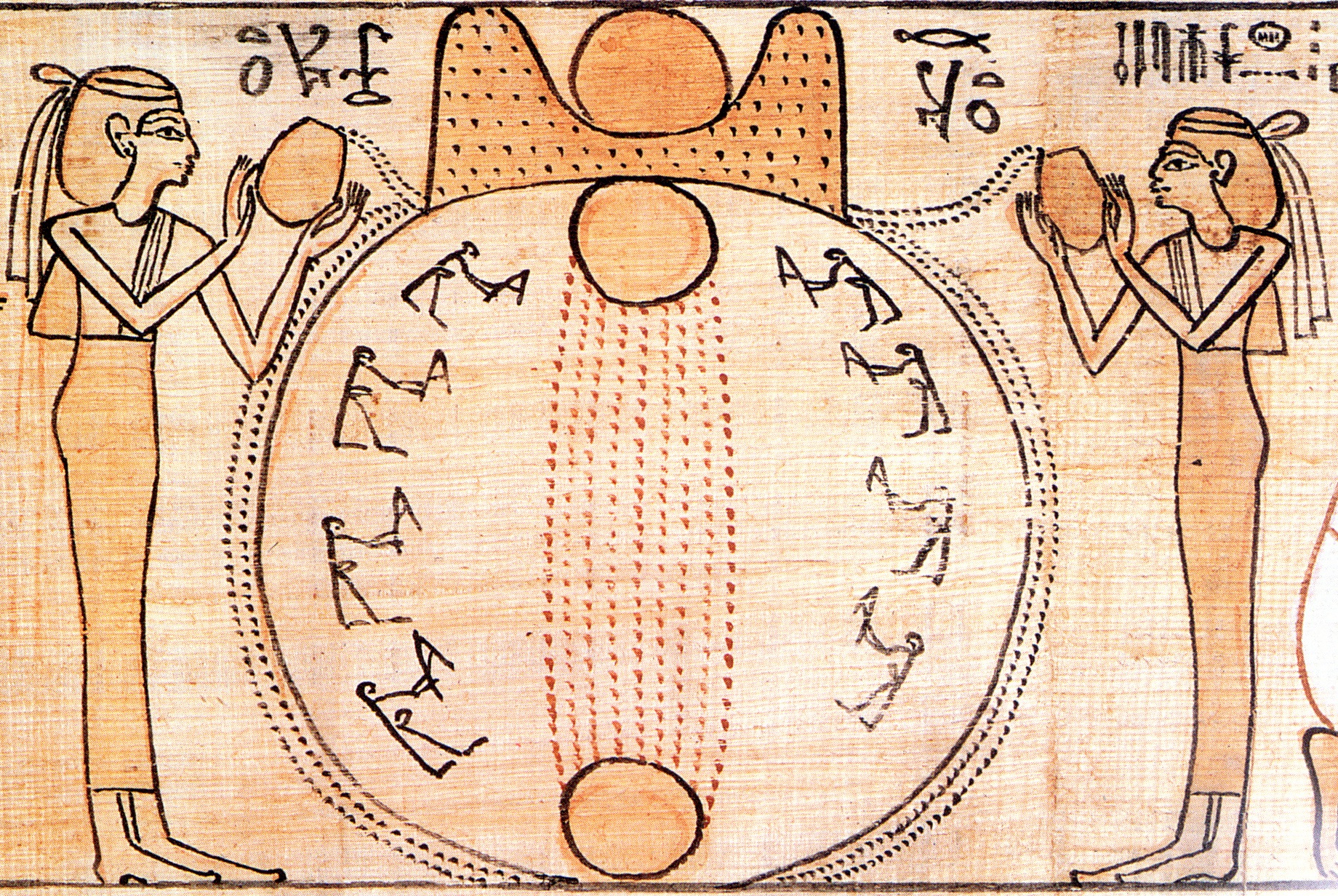

Within this interval, the world receives its order; the cycle of day and night, the rhythm of seasons, the twelvefold partition that will become the zodiacal belt. Heliopolis is city and clock; its columns, its obelisks, its altars, all mark the axes along which the heavens turn, and by which time itself becomes legible to human striving.

III. The Drama of Manifestation: The Ennead and the Perennial Pattern

From the union and separation of Geb and Nut emerge the famous Ennead, the company of nine deities whose lives and deaths embody the tragedy and triumph of the world. Osiris, Isis, Set, Nephthys, and Horus unfold from the earlier dyads, each enacting a particular aspect of becoming: sovereignty, wisdom, dissolution, boundary, and restoration. These Gods, far from being mere personifications, are archetypes of process, mirrors within the Mirror, faces of the eternal return.

The myth of Osiris and Isis, so profoundly woven into the Egyptian funerary rites, is a recapitulation of the world’s origin: Osiris dies and is scattered; Isis gathers the fragments and weaves them into new life; Horus avenges and completes the work. In every ritual, in every burial, this cycle is repeated; the soul descends into the underworld (Duat), encounters its own reflection, and emerges transfigured. The Ennead is not a pantheon, but a grammar of manifestation, a constellation that prefigures the Sephirotic tree, the planetary powers of the Magi, the dance of planets through the houses of fate.

The architects of Heliopolis understood, as did the Sufi poets and the Platonic philosophers, that myth is a map; that the journey of gods is the journey of souls. In the rites of passage, the weighing of the heart, the recitation of secret names, the perennial pattern emerges: unity veils itself as multiplicity; death is the gate of return. The city of the Sun stands as the world’s axis, the mirror by which every later tradition measures its own circumference.

Astrologers, inheritors of this wisdom, read in the Ennead the logic of the chart: the Sun’s daily rebirth; the division of the sky into twelve houses, four gates, and a hundred doors; the procession of hours and the rule of the ascendant. The separation of Nut and Geb is re-enacted in the horizon’s division at dawn; Atum’s contraction in the focusing of the moment of birth; the Ennead’s cycles in the slow passage of planets across the spheres.

Epilogue: The Seal of the Sun

The myth of Heliopolis endures as an operative pattern, a mirror into which every later theurgy gazes and finds its own reflection. Beneath the Rose windows of Chartres, beneath the Sefirot and the Great Chain of Being, the old logic persists: contraction, separation, and return. The temple, the city, the chart, and the tree all align beneath the same sun; each marks an hour in the world’s unfolding.

To open the gates of Heliopolis is to awaken to the perennial dawn: to stand at the axis of the world, where the One becomes Many and the Many yearn for reunion. The rites endure; the myth remembers; the city of the Sun casts its shadow, long and golden, across every threshold of the spirit.

Fiat lux.