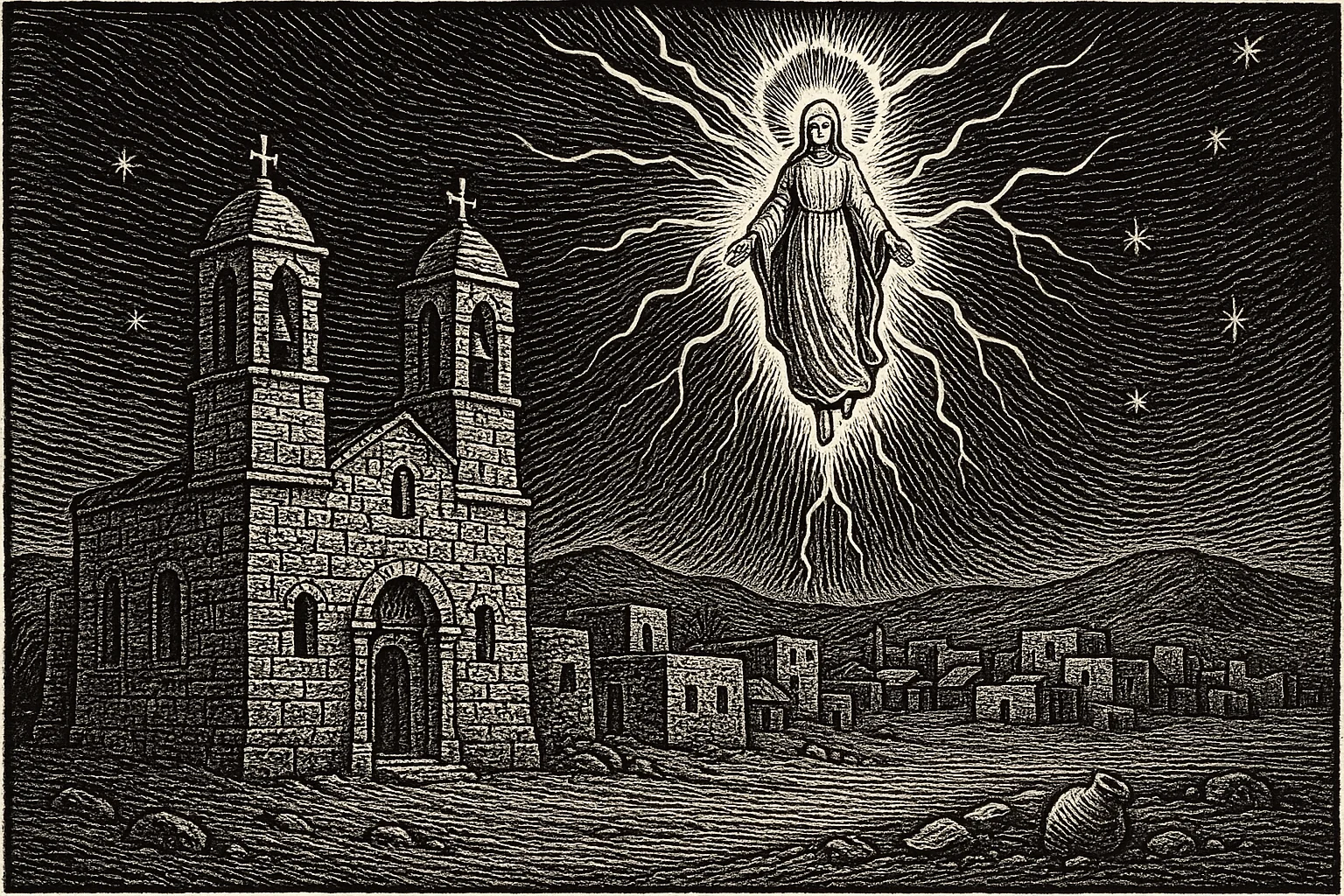

Some events serve not to comfort the flock, nor to reinforce the orthodoxy of temples. They tear the veil of the world and return the sacred to its primordial astonishment. The Coptic Marian apparitions are not miracles in any catechetical or pious sense; they are operational breaches in the wall of reality, visiting communities on the fringes of power, beyond the radar of the great Church, far from Roman hegemony. In Egypt, on soil where the sand still hides fragments of the oldest gnoses, the Feminine archetype emerges when the night is longest and abandonment seems total.

The episode of Zeitoun (1968–1971) is merely the most visible point in a web of manifestations that stretch from the earliest centuries of the Christian era to the present. The Lady appears not as flesh, but as pure light, hovering over the church dome, visible to crowds of all confessions: Copts, Muslims, Jews, agnostics, children and elders, state officials, army officers, illiterate women and engineers. There is no formal message, no dogma, no secret revealed nor prophecy repeated. Only presence. Only a Sign. And it was not the first time: lesser-known reports tell of similar phenomena in Assiut (2000–2001), Warraq (2009), Shoubra (1986), and even in forgotten villages of Upper Egypt during periods of persecution. The pattern is always the same: social crisis, collective fear, threat of annihilation and, suddenly, the eruption of a Woman of light, not claiming any altar for herself, demanding no conversion, not even speaking.

The Gnostic gaze reads in this phenomenon a fierce critique of theology as possession. The Mystery lends itself neither to explanations nor to those who build walls around faith. Sophia, Mother of the Living, is an unsettling presence, never the property of hierophants. The silence of the Lady of Zeitoun is more eloquent than a thousand verbose apparitions at Fátima or Lourdes. The absence of speech, of secrets, of threat, rejects the logic of the miracle as reward for the “good believers.” Here, the Lady manifests to all, without barriers. She makes no distinction between pure and impure, orthodox or heretic. She founds no new Church, legitimises no doctrine, sanctions no temporal power.

Historically, it is impossible to dissociate Zeitoun from the Egyptian context after the Six-Day War. The country, shattered in its sense of self, witnesses the irruption of the impossible. The secular state attempts to control, the religious authorities hesitate, but the phenomenon escapes all regulation. The official accounts themselves diverge: witnesses describe “white fire,” “living light,” a “female silhouette with a dove,” and even cures and sudden changes in the environment. Nasser’s government, fearing religious riots, sends in soldiers; the crowds grow night after night. Journalists, photographers, sceptical doctors, Muslim imams, Jewish rabbis: all see, all fall silent before the inexplicable. The Lady leaves no forensic proof, but leaves an open wound in the rationalism of the state.

This silence is a Gnostic key. The great Gnostic texts, from the Gospel of Thomas to the Pistis Sophia, suggest that truth is not transmitted in words, but by direct contact, by illumination. Mary, in Gnosticism, is less “Virgin” in the dogmatic sense and more Sophia incarnate, epiphany of the Feminine principle that heals, unites, and subverts. Zeitoun stages the irruption of this primordial energy: not as dogma, but as the raw experience of the Sacred. Whoever tries to interpret misses the point. Whoever desires to catalogue errs. Only those who contemplate, and accept not-knowing, experience true epiphany.

One cannot ignore the subversive power of the phenomenon. The Coptic tradition, historically marginalised, heir to Pharaonic Egypt, has remained on the threshold of heresy for centuries. The Marian apparitions, witnessed also by Muslims, become a scandal for every religious identity. Gnosticism recognises this shock: Sophia belongs to the margin, the interval, the unconsecrated space. At Zeitoun the crowd dissolves the invisible walls of separation. Believers of different faiths pray together. The Sacred is no longer anyone’s property. In the streets of Cairo, theology is disarmed before the enigma.

The mystical Jewish thread is subtly interwoven with the Coptic phenomenon. Cairo was, for centuries, home to one of the richest Jewish communities in the Islamic world, where kabbalists, rabbis, poets, and physicians cultivated the hidden presence of the Shekinah. In Jewish tradition, the Shekinah is the divine dwelling, the Feminine aspect of God, manifest as light, glory, cloud, or fire. Many texts from the Zohar and the cabalistic schools of Spain and Egypt speak of the Shekinah descending upon the community when it is in exile, in mourning or in celebration and whenever the Sacred is threatened by forgetting.

There are reports in the Cairo genizah, the treasure trove of Jewish manuscripts discovered at the Ben Ezra synagogue, of mystical experiences shared by Jews and Copts: visions of lights in cemeteries, apparitions of Female figures during hours of prayer, accounts of healings and signs that could not be claimed by any single faith. For the kabbalists of Cairo, the Shekinah wandered the city, entering homes, hovering over synagogues, and, on special nights, mingling with Christian and Muslim festivities. Accounts by Sephardic mystics speak of encounters with “the Lady of Light,” who cannot be captured by any rite, but manifests as both consolation and judgement.

In this subterranean Egypt, where the presence of the Shekinah touches all who live at the margins, the Coptic Marian phenomenon gains an unexpected resonance: the Lady of Light who hovers above Zeitoun, visible to all, is a living symbol of this Hidden Feminine which unites traditions, traverses rituals, and rejects all exclusive claims. For both Gnostics and kabbalists, there is no contradiction: Sophia and Shekinah are reflections of the same primordial matrix, the Wisdom who visits the exiled, the widowed, the persecuted. In the texts of the Zohar, the Shekinah reveals Herself most fully when Israel is in suffering, when prayers are made in tears, and when exile seems endless, precisely the scenario of the apparitions in Zeitoun, Warraq, and Assiut.

The festivals of Lag BaOmer, celebrated in Cairo for centuries, were marked by nocturnal vigils, where Jews invoked the presence of the Shekinah as a dancing fire above the heads of the faithful; a tradition that echoes Christian Pentecost and closely resembles, in imagery, the manifestations of light in Marian apparitions. On certain nights, it was said that the Shekinah would even visit Christian churches, leaving signs for all the children of exile. Not by chance, stories of conversion, shared dreams, inexplicable healings, and reconciliations appear in both Jewish and Coptic accounts, always linking the luminous Feminine presence to the journey across the Spiritual desert.

Ultimately, the phenomenon of the Coptic Marian apparitions is also an echo and continuation of this heritage. There is no absolute separation between Sophia, Shekinah, Barbēlō, or the Holy Spirit: all are faces of the Presence that wounds reality, returns the world to Mystery, and defies any regime of possession. Zeitoun is a new page of the same secret book, read in silence by Copts, Jews, Sufis, and even non-believers who cross the Egyptian night in search of what has no name.

In the end, the apparitions of light upon the domes of Cairo become testimony to a single truth: the Hidden Feminine passes through all traditions, refusing to be domesticated by any. The Lady of Silence is also the wandering Shekinah, the Sophia of the Gnostics, the Moon of Israel, the fire that does not consume. The Mystery remains and is revealed, again, only to those who contemplate, without possession, without answer, the abyss of Light.