What follows is not biography, nor a claim to truth. It is not a portrait of a man, nor a chronicle of facts. The name Josh Homme is here adopted as mask, as sigil, a vessel through which the drama of rupture and return may be observed. The events described are understood as allegory, not evidence; as ritual, not history. This reading rests upon the hermetic premise: every life, at its most feverish point, becomes archetype.

What occurred to this musician is received here as emblem. It matters little whether the heart stopped or the mind wandered; the value lies in the echo of the myth that is retold in each collapse, in each return from darkness. This is not a story of music, but of the Music of the Spheres, of the loss and potential return of that which the ancients called harmonia mundi, the hidden order that sustains both cosmos and soul.

There exists, in the deepest strata of Western tradition, a doctrine that claims the universe is not mute, but endlessly resonant. This is the secret of the ancients: that beneath all movement, all form, there resounds a hidden harmony. A music inaudible to mortal ears, yet shaping all that breathes, decays, and returns.

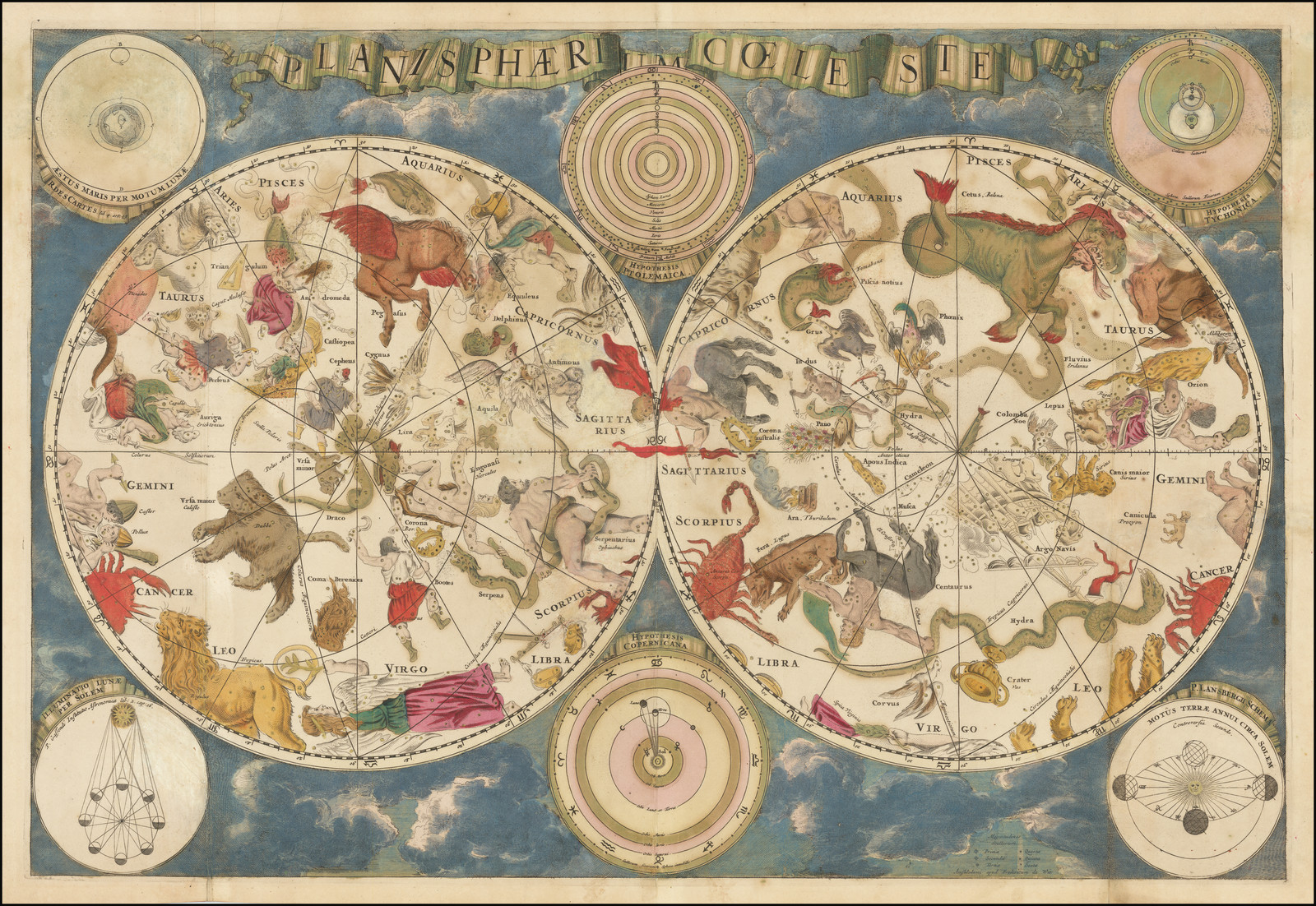

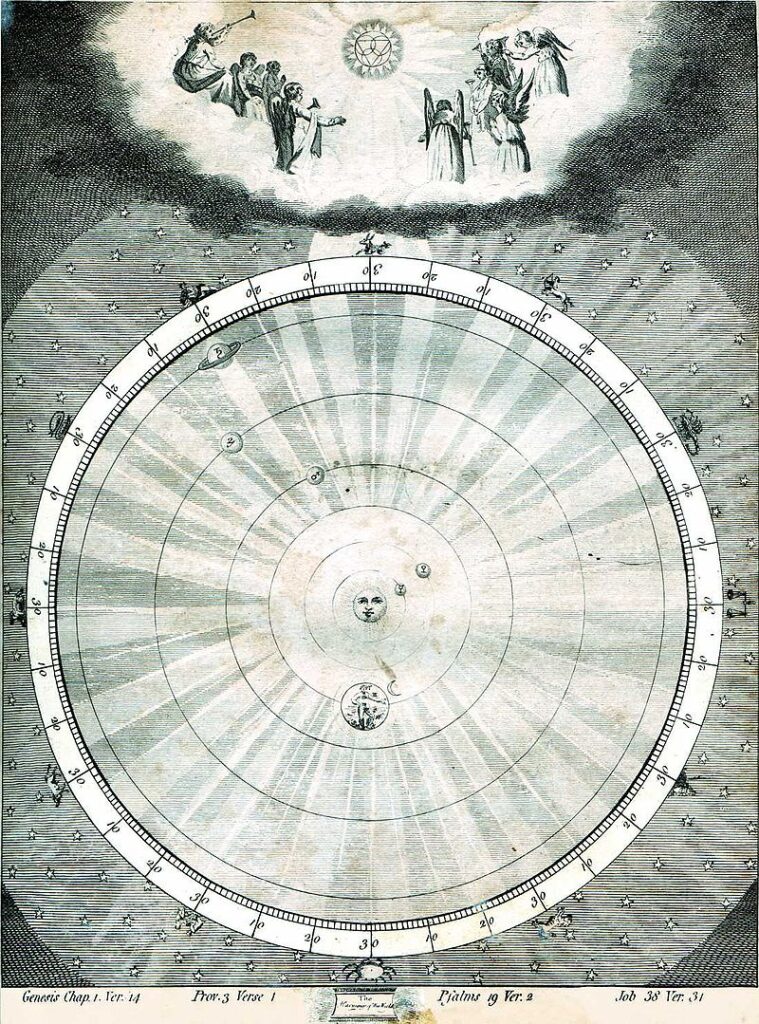

This is the Music of the Spheres (Musica Universalis), first spoken by Pythagoras, echoed by Plato, and woven through the soul of every hermetic, and neoplatonic current. The teaching is this: Each planet, each star, each turning of the firmament, issues a note. These notes, perfectly tuned to the divine ratio, form a silent song that orders both cosmos and psyche. The Sun sings in gold, Saturn in lead, Venus in copper; each a vibration, a secret word, an invisible interval.

To the philosophers, this celestial music is not metaphor, but the actual substance of order. For Ficino, to tune the soul was to align it with the cosmic song, to become an instrument through which the harmonies of the above might resound in the below. The soul, thus tuned, becomes a participant in the liturgy of the heavens, receptive to inspiration, prophecy, and gnosis.

Yet the Music of the Spheres is not easily heard. The gnostic myth tells of a descent, a forgetting: the soul enters the world through the planetary gates, each imparting its signature, each weaving forgetfulness. To hear the music is to remember the place of origin, to escape the static of the mundane and recover the primordial chord. For the Hermetist, every true act of art, magic, or creation is an echo of that first harmony. To lose touch with it is to fall into chaos, to become deaf to the order that sustains both cosmos and mind. Hence Natascha Shneider’s “DJ” snippet in Songs For The Dead:

This is W.O.M.B, the womb. And if you, my pets, learn to listen, I’ll let you crawl back in. Here is something you should drop to your knees for, and worship. But you are too stupid to realize yourselves.

This is not mere interlude; it is annunciation. Here the Feminine speaks as the Gate, the matrix of origin, the mouth of the Lady who governs both birth and return. In the ancient mysteries, to enter the womb is to re-enter the temple: the sanctuary of dissolution, the lunar vault, the place where the voice of the spheres becomes audible only to those who surrender the arrogance of their surface self.

She who speaks in the album is not a character, but a veil. Her words reveal the law of the initiate: only those who kneel before the threshold, who listen with more than the ear, are admitted to the hidden music. To be “too stupid to realize yourselves” is not an insult, it is the gnostic diagnosis of forgetfulness, the human condition. Most remain deaf, blind, spinning outside the sanctuary, unaware of the channel that pulses beneath all noise.

Thus, the true descent, the true ordeal, is to be expelled from this womb: to lose the music, to wander outside the voice, to yearn for return. But entry is not by force, nor by intellect. It is granted only to those who learn to listen, as one listens for the music of the spheres: with the whole soul, with longing, with humility before the Lady’s threshold.

Astrology, too, is founded upon this principle: the sky’s movement is not random, but orchestral. To read a birth chart is to decipher the score written at the hour of incarnation, the unique configuration of notes that governs each destiny. This is the crucis that underpins the myth of the artist, the mystic, the visionary. Those who create are not inventors, but receivers.

To be cut off from this music, as occurs in every true ordeal, is not merely to suffer silence, but to lose access to the axis mundi itself, the vertical thread that binds time to eternity.

Spinning in the Daffodils: The Eclipse of the First Musician

In the symbolic desert, the true initiate is not the one who speaks, but the one who listens. The myth opens not with the artist at work, but with the ear attuned to a secret vibration. The figure known as Josh enters this tradition not as an innovator, but as one who, for a time, found his pulse aligned with the celestial mechanism. The works that emerged with Kyuss and/or Queens Of The Stone Age – harsh, incandescent, singular – did not arise from effort, but from the privilege of proximity: the artist as satellite, the human soul as receiver of the hidden concord between above and below.

Them Crooked Vultures evokes Saturnian birds circling the remains of the past. This is not a new band, but a coven; not a continuation, but a ritual of recollection. The thread that binds the work is the presence of the channel Josh, whose artistic daemon is both summoner and summoned. The music is forged in his image, though refracted through the legends at his side.

It is important, then, to see this record not as a branch, but as a final flowering, an autumnal harvest at the edge of winter. Each track pulses with the residual energy of QOTSA, but here that current is interrupted, bent into new shapes, seeking something just out of reach. And it culminates in Spinning in the Daffodils, a song that does not end, but dissolves, not with fire, but with the cool, slow breath of piano.

John Paul Jones, once architect of Led Zeppelin’s immortal echo, here becomes psychopomp: his piano sequence at the close of the record becomes a réquiem, not just for the project, but for the spirit of the composer himself. From a gnostic perspective, the requiem is a descent: the soul preparing to cross the boundary between plenitude and privation. It is the moment Saturn claims his due, halting the progress of the Sun.

In the anatomy of Spinning in the Daffodils, before the requiem in piano, a section appears that was not born for this record alone. This passage had been composed earlier, in tandem with Mark Lanegan, for the aforementioned Songs For The Deaf, an album already haunted by symbolism, mysticism and absence, deserving its own separate inquiry.

The presence of Lanegan is not accidental. In this track,he is the living shadow, the double-headed eagle to Josh’s solar crown. Where Josh embodies the force of the noon sun – the visible, the fiery, the sovereign -, Lanegan moves like a lunar echo, sombre, prophetic, subterranean. Together they do not simply harmonise; they enact a ritual of duality, a drama of Sun and shadow, Self and daimon. This duality is not only structural but openly confessed. In I Wanna Make It Wit Chu, Josh sings:

“You wanna know if I know why

I can’t say that I do

Don’t understand the evil eye

Or how one becomes two”

Here, the riddle of the sun and the moon, of unity and division, is uttered in plain sight. The “evil eye” is not just misfortune; it is the gaze of the Other — the daimonic mirror that splits the soul, revealing the shadow within the light. So it is in Spinning in the Daffodils: the section co-written with Lanegan functions as a threshold, a corridor between cycles. It is a visitation from the realm of the dead, a passage across the night-sea.

Mark’s phantasmagoric presence marks the moment when the creative solar channel is forced to confront its own lunar reflection; the shadow, the wound, the counterpart. Only after this encounter does the song spiral into the final, wordless piano: a requiem, a surrender. This structure is not incidental. It is the drama of the Orphic: descent, encounter with the underworld double, and dissolution. The sun descends, the moon rises. The channel is broken, and the rite proceeds.

The daffodil does not bloom for the world. Its golden trumpet opens toward the void, a herald that faces not outward, but down and in. In the lore of the Western mysteries, the daffodil is more than a flower: it is an emblem suspended between death and renewal, a cipher that marks the threshold of all descent.

In the mythic order, the daffodil belongs to Persephone. It is the lure that draws her to the underworld: while gathering daffodils, Persephone was seized by Hades and led below, the first flower of spring becoming the gateway to loss. Thus, the daffodil becomes the flower of abduction, a sign of innocence drawn into shadow, the herald of the journey from visible world to hidden realm.

But there is a deeper resonance: the daffodil is narcissus. Named for the youth who drowned in his own reflection, it is the flower of self-regard, of spiraling identity. Narcissus dies not from love, but from the gravity of his own gaze. The daffodil springs where he fell: a monument to the fatal loop of self-contemplation.

In the Hermetic and alchemical current, the daffodil is a threshold bloom.

It blossoms at the pivot between the nigredo and the albedo, between dissolution and return. Its yellow is not mere brightness, but the sign of mercury rising through the darkness: the solar force, fragmented, searching for reintegration. To “spin in the daffodils” is to circle at the edge of transformation, caught in a liminal dance, neither lost nor redeemed.

The daffodil holds the echo of Venus exalted in Pisces, the flower that promises beauty but conceals sorrow, the renewal that is never unshadowed. It signals the time of endings that are beginnings, cycles that close by opening elsewhere. For Josh, to be “spinning in the daffodils” is to orbit the site of his own eclipse. It is to dwell in the field where the goddess vanished and the youth dissolved, to be present at the moment the soul is taken below.

Adhuc iter est.