Languages do not die. The words uttered in temples and deserts remain suspended in the subtle air, their syllables repeating themselves in the invisible. Each sacred tongue becomes a vessel of vibration; through long use it condenses into a presence, a field of memory. The prayers of the dead stratify the astral atmosphere, forming egregores. These fields are acoustical bodies of faith, born from centuries of repetition, tears, and rhythm.

When we recite an ancient prayer in Latin, Hebrew, Coptic, or Sanskrit, our voice aligns with a current that has never ceased to flow. The sound is like a stylus resting on an old vinyl record; the grooves are there, carved by devotion of those who came before us. We become a reed through which the tradition passes. What matters is not belief but tuning. Each of these languages carries a geometry of sound; vowels and consonants are proportions of the world’s own music. They mirror the architecture of being.

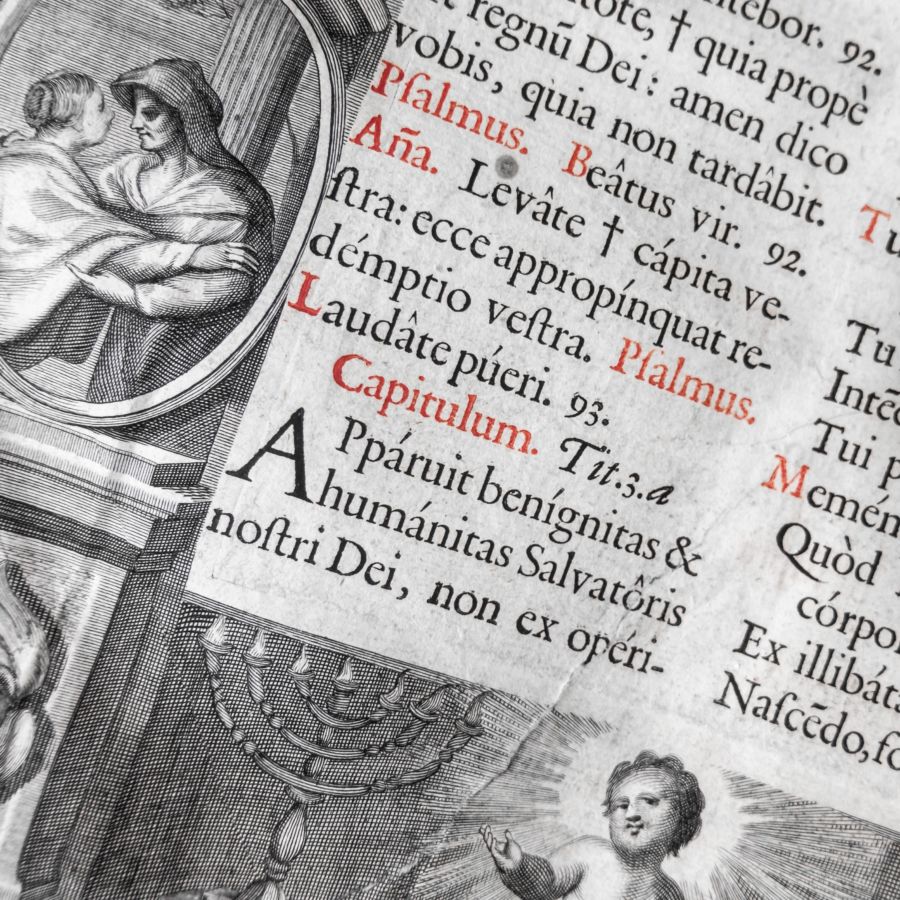

Latin was the cathedral of the West; Hebrew the alphabet of Divine creation; Coptic preserved the murmur of Egyptian sanctuaries; Sanskrit crystallised the breath of the Vedas. When the human mouth utters these ancient shapes, it repeats gestures already traced in the air inumerous times. The astral substance responds because it has learned those shapes. The air itself recognises them.

Modern tongues lack that Spiritual weight. Their words have not been sung through cloisters or painted on parchment with tears. They are instruments of commerce, flexible and quick, but poor in resonance. Whenever we use a sacred tongue, we enter a cathedral of sound. The space between syllables carries the memory of incense, bells, and breath. The more a language was prayed, the more its field thickened. The astral world does not understand grammar, but it surely understands frequency.

The Latin Pater noster, the Hebrew Shema, the Coptic Agios o Theos, and the Sanskrit Gayatri are engines of alignment. They are webs of vibration. If we speak them, we rejoin the long continuity of invocation that binds the visible to the invisible. The sound gathers, condenses, and rises again, carrying the soul upward through the echo of its ancestors. A Sacred language is therefore an instrument of ascent, built from the faith of countless mouths.

II. The Word as Order

The Latin root of oratio is orare: to speak, to plead, to address the Divine. Its older ancestor is os, oris, the mouth. The mouth was seen as the first altar of the world. From it came breath and, from breath, sound; from sound, the cosmos. To speak was to align the inner wind with the rhythm of the stars. Ordo means order, the arrangement of parts into harmony. And orare and ordo belong to one family of symbolic meaning. To pray is to place oneself in order through sound.

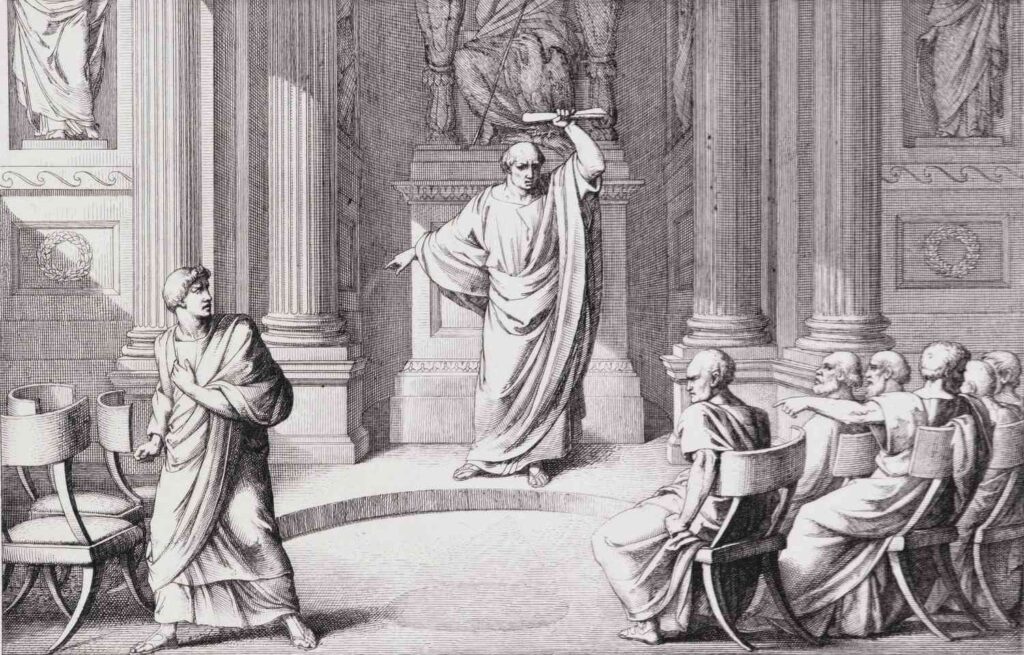

Cicero, who filled the Roman Forum with orationes, was not merely a politician; he was a magician of rhythm. A pure magus. He knew that persuasion depended on cadence, that words moved minds because they echoed the pulse of the world. The ancient orator stood between the human crowd and the invisible powers that listecned above. Speech was a rite and not a mere performance. The orator channelled the same current that later priests would direct toward heaven. When the Romans used the word oratio, they meant prayer and discourse because both were acts of invocation.

The movement of the mouth is a cosmic act. Breath passes through the vocal cords like wind through an organ pipe, striking the air and leaving a mark. Each prayer is a sculpture of sound. When uttered with intention, it re-establishes the hidden order between body and Spirit. The faithful who recites the Credo in Latin is not just explaining belief; he is re-creating the structure of faith within the music of the body.

The orator and the mystic share one art: the creation of order through voice. To speak rightly is to build and to distort language is to collapse structure. The ancient world feared the misuse of speech because it altered the equilibrium of realms. Magic requires the mouth. The same power that forms sentences can form realities. It is not by chance that several monastic Orders impose vows of silence, not as punishment but as liberation from the danger of speaking amiss. The Carthusians embody this understanding: silence is their safeguard, as they know that each word is a seed of form, and an ill-shaped sound can unmake harmony.

The prayer is pure architecture in motion; the mouth becomes compass and chisel. To pray is to construct invisible geometry, and the word becomes the column of light that links man to the gods.

III. The Wound of the Rite

When the Latin tongue was removed from the Catholic Mass, something immense fell silent. Reformers sought clarity, wishing the faithful to understand each word; in doing so they dismantled the organ of vibration that had bound the Western soul for fifteen centuries. Latin was never a barrier; it was a resonator. Its syntax was stone; its vowels were glass; its consonants, iron. The old rite did not require comprehension; it required participation in sound. It is no coincidence that on Mount Athos the Greek tongue remains untouchable: the monks know that a sacred language is a matter of vibration, and that, once its resonance is broken, the body of prayer itself fractures.

A sacred language works through resonance, not explanation. The ear surrenders, the body enters the cadence and meaning descends through rhythm rather than reason. When the priest intoned Dominus vobiscum, the faithful responded Et cum spiritu tuo; the exchange was a vibration of mutual recognition between worlds. The Latin words formed an acoustic bridge. The shift to the vernacular replaced chant with commentary. The mystery became plain speech and plain speech cannot bear the same weight.

The Latin liturgy had generated an immense field of accumulated sound. Cathedrals were tuned to it. The stones had learned those frequencies. When the tongue changed, the resonance fractured. The air once filled by the long vowels of Kyrie eleison now holds phrases that remain motionless. The loss was metaphysical.

The abandonment of Latin was therefore a rupture of continuity. The West lost its tuning fork. The cosmic rhythm once sustained through the Mass became dispersed among many tongues. Where there was unity of sound, there is now multiplicity, dispersion, the opposite of true symbolism. But the current still exists. Whoever utters the ancient words with a quiet heart will feel the vibration return. It begins as a subtle trembling in the chest, spreading through the spine until the whole body remembers the rhythm of the old rite.

The sacred languages remain, each a constellation of sound. Their power does not depend on institutions. When spoken again with reverence, the syllables reopen the path between breath and Spirit. To pray in Latin or Sanskrit is to step back into the geometry of origin, where the Word was substance. The sound carries the memory of creation. The faithful mouth becomes what it was meant to be: a small yet perfect instrument of the Logos.

Κύριε ελέησον