There is a sentimental image of the monk as a fragile old man hiding in a monastery, running from the world out of tiredness, fear, or inability to live. It comes from not understanding what asceticism is. This is clear in the word itself. Asceticism comes from the Greek áskesis. It is training, exercise, discipline. It is the word used for the training of the athlete too. The verb askein means to exercise, to work, to shape by repetition. The ascetic is someone who enters a regime, a demanding way of life, working on themselves continuously. The etymology destroys the fantasy of the monastery as a refuge for fugitives. The monastery is, from the root of the word, a place of training.

No one becomes an athlete only by mere inspiration, enthusiasm, or illumination. People do it through repetition, rule, regime, obedience to a form. Early Christianity takes up this image without embarrassment. Saint Paul speaks of running in the stadium, of fighting, of struggling, of not fighting against the air (1 Cor 9:24–27; 2 Tim 4:7). The Desert Fathers call themselves athletae Christi, athletes of Christ. The monastery is a gymnasium (gym) of the soul, from Greek gymnásion, from gymnós, “naked”, the place where the soul is stripped in order to be trained. A place of work, effort, discipline. A place where a form is accepted and held day after day.

Against whom do these athletes compete, then? Not against others. Not against the world. Not against “sinners”. The fight is against what in us does not coincide with ourselves. Against dispersion. Against inertia. Against fantasy, from Greek phantasía, from phaínein, “to make appear”, the same root as phantom, because it produces appearances and phantoms that occupy and disturb the imaginal organ. Against the automatism of desire. Against the laziness of attention. Against the tyranny of states over substance.

The tradition calls this the passions, the pathē. That which happens to me instead of what I do. That which moves me without my moving it. That which uses me. The ascetic refuses to be a bundle of reactions. He wants to be an agent. He wants his being-in-a-state to obey his being, the old Latin difference between esse and stare, between what one is and how one stands or finds oneself at a given moment. This is the same level at which God says to Moses “I am who I am” (Exodus 3:14), and at which Christ says “before Abraham was, I am” (John 8:58); in both cases, being is affirmed without reference to any state or condition. It is not a way of being. It is being itself. Also comes to mind the Greek link between being and ousía, which means substance: what truly is, what exists in itself and not as a passing condition, what remains while states change. The monk wants his life to stop being ruled by impulses, moods, images, reflexes.

For this reason the fight is interior. Evagrius Ponticus describes the eight logismoi. The thoughts that disorganise the soul. Later this becomes the seven capital sins. These are forces of deviation, dispersion, of the old fall into the multiple, into the automatic. The monk is an athlete because he wants unity. He wants to stop being ruled by many different masters. He wants the intellect to see, the will to will, the desire to desire, in one direction only.

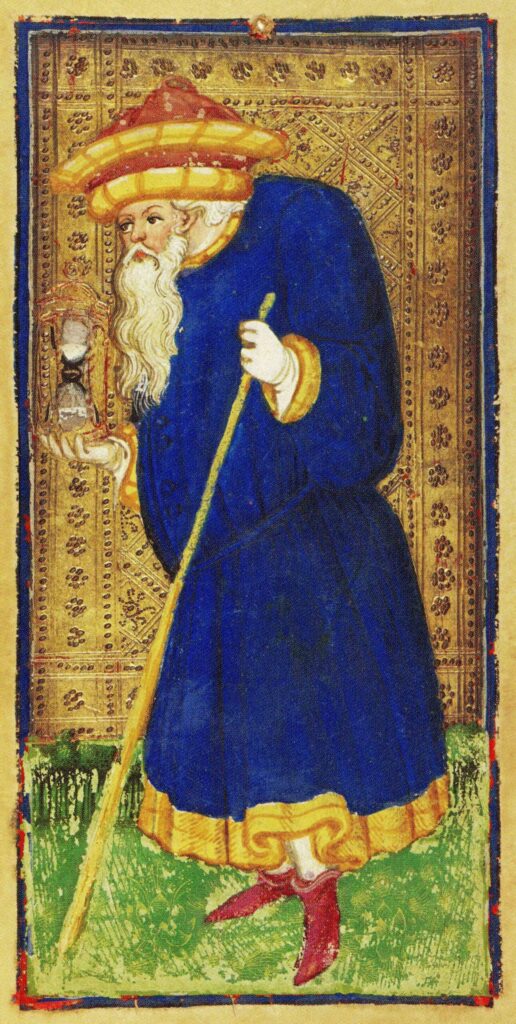

This same structure is visible in the Hermit in the Tarot, the ninth Major Arcana, the card of initiation. The lamp he carries is a lamp of descent into one’s own being. It illuminates the inner caves. It does so through a sober, mental, analytical process, like the work of the monk. This is why the card is associated with Mercury in Virgo, Hermes exalted in his earthly form, Virgo being a sign of earth, without wings, turned toward scrutiny of the interior. And it echoes the line of Psalm 119: “Thy word is a lamp unto my feet, and a light unto my path.” The athlete trains to be able to carry this lamp as well.

Monastic life was never a flight from the world, but a strange war. There ano outer lands to conquer. It conquers unity whilst bringing down habits. It kills automatisms. Also, every athlete trains for a form, a model, a measure. In Christianity, that measure is Christ. Not as a mere moral ideal. As the form of a human being coincident with himself and with God. The ascetic trains so that his life may take that form. In the end, the fight is always the same. Against dispersion, against the tyranny of everything in us that prefers inertia to form.

Kύριε ελέησον