When the soul stands at the border of the unsayable, certain presences arise, subtle and unyielding, weaving themselves through the marrow of the day. In the cloisters of ancient Egypt, between the sand and silence where speech dissolves and the heart sits waiting for visitation, the Fathers of the Desert charted out a region of Spiritual geography where the very air grows heavy with absence. To this landscape, the Roman world gave few names; Cassian, whom the West remembers as Johannes Cassianus, gave it the name acedia. The word shivers through the centuries, a cipher only for those who have tasted the bland terror of a noon that will not end, a torpor which is neither fatigue nor despair, a stillness that seethes.

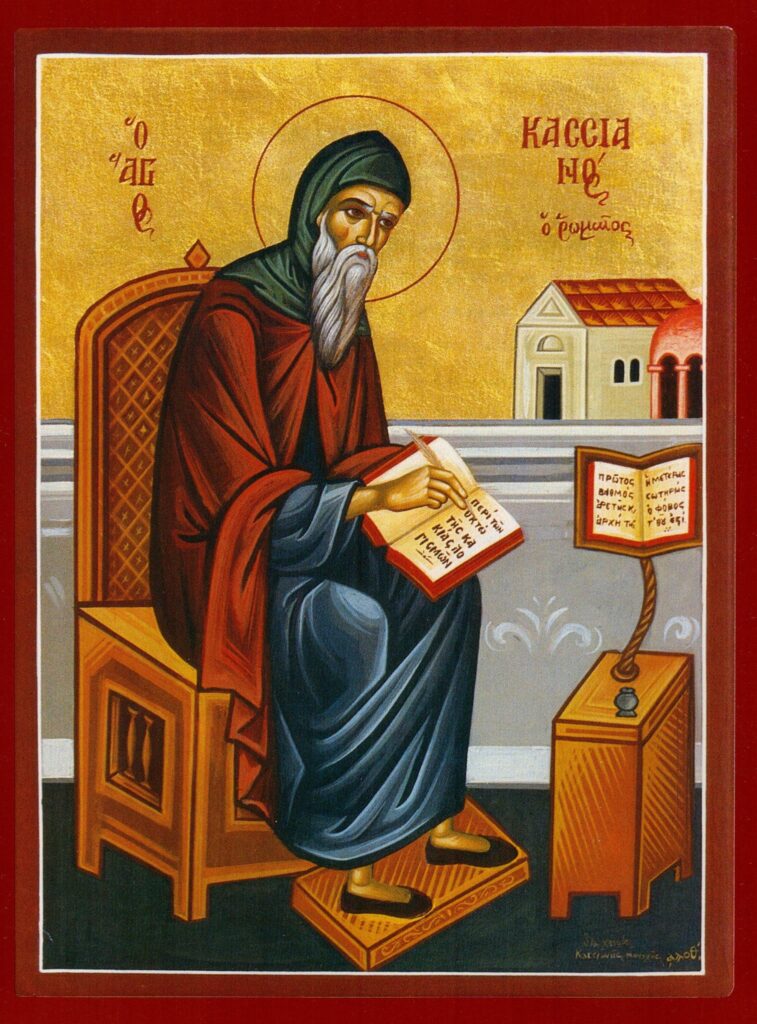

The acedia is not merely a mood, nor a fault of the flesh, nor a clinical malaise; it is a visitation, a Spirit of the threshold, as ancient as monasticism and as modern as the blue-lit vigil of the insomniac. In the annals of Christian mysticism, Cassian is the cartographer of this inner desert; a mystic who, unlike the physicians of the body, sought to name the shadows that rise when the Divine voice falls silent. His Conferences and Institutes, written in the fifth century and revered in both Eastern and Western traditions, remain among the most precise documents on the topography of the soul’s afflictions. Cassian’s acedia is more than historical curiosity; it is a living key, a pressure of Spirit upon the vessel which has yet to become a true conduit.

I. The Liminal Spirit: Acedia as Visitation

Acedia is often rendered as “sloth” in the catechisms of later centuries, but this translation betrays the phenomenon’s true nature. Cassian, drawing on the wisdom of the Desert Fathers such as Evagrius Ponticus and Macarius of Egypt, describes acedia as a daemon meridianus; the noonday demon, a presence that seizes the ascetic in the full glare of the sun. It is neither lassitude nor indolence, but a restlessness charged with despair and agitation. In Conferences X, Cassian recounts that the monk stricken by acedia finds the very cell intolerable, the hours impossibly long, the Psalms tasteless, the body heavy, the mind scattered and voracious for diversion.

In this space, the silence of God is as an absence which wounds. The ancients saw in acedia a liminal Spirit: an entity or force encountered at the very boundary where the desire for union with the Divine meets the resistance of the flesh, the finitude of form. The boundary is real; it is where the profane falters, and the conduit is tried. Cassian’s portrait of the afflicted monk is not moralising; it is diagnostic, even surgical. The visitation of acedia reveals the fragility of the soul before the abyss of the Real. It uncovers the impurity of intention, the unresolved desire for escape, the impatience with the tempo of Divine absence. For Cassian, acedia is a trial, an initiatic visitation which can either render the vessel more transparent to Spirit, or fracture it in bitterness.

II. The Language of the Desert: Reading the Void

The landscapes described by Cassian are not merely physical. In his writings, the desert is perpetually a figure for the region of the soul where language fails, and the self is stripped of comfort, distraction, mask. The acedia which arises in this place is a language of pressure: the presence of the invisible manifest as weight, delay, inertia, and craving for elsewhere. In Institutes X, Cassian warns that the monk beset by acedia is tormented by the thought of leaving the cell, of changing places, of pursuing any stimulus that may relieve the weight of the void.

The temptation is towards flight; a refusal to dwell, to endure, to be present. The soul, denied the sensible consolation of Divine presence, is left exposed to its own lack, to the bare nakedness of a desire that no longer knows what it seeks. Contrary to the later moralists, Cassian does not prescribe a frantic battle with the demon; instead, he counsels fidelity to the cell, patience with the hour, acceptance of the void as language. The monk is to remain, to persist, to allow the silence to become articulate. In this, Cassian is closer to the alchemist than the moralist; the true transformation is achieved not by force, but by exposure and endurance. The void speaks; it is, for those who know how to listen, the pressure of the Real inviting transfiguration.

III. From Trial to Conduit: Acedia and the Modern Soul

To read Cassian today, under the relentless glare of a world more restless than any desert, is to hear a familiar Spirit whispering in the fibres of contemporary life. Far from an extinct monastic malaise, the acedia is present in the restless ennui of the age: in the hunger for diversion, in the loss of appetite for the Sacred. Restlessness often arises where the soul has become unrooted, where the cell is no longer a place of dwelling but a prison. The parallel is exact. In the ancient cell, the acedia revealed the impurity of desire, the incapacity to bear the pressure of Spirit unmediated by comfort. In the contemporary psyche, anxiety reveals the same: an incapacity to dwell, to wait, to attend to the invisible without escape. Cassian’s wisdom is that acedia is not punishment, but portal. The pressure is the sign of an encounter; the void is the threshold of the pathway. The Spirit presses not to destroy, but to hollow out a vessel able to receive.

Coda: Cassian, Cartographer of the Silence

Between the spoken word and the silence that follows, Cassian stands, attentive, a scribe in the house of absence. His name survives not because he mastered the void, but because he gave it a language; he recognised in the noon-demon the hand of the Spirit, sculpting vessels through pressure and tribulation. His legacy is an invitation to remain in the silence, to endure the presence of absence, to allow the pressure of the Spirit to shape the conduit. The acedia remains. It is not a pathology to be medicated, but the Spirit-liminal which guards the crossing from habit to offering.

Fiat Lux.